A cloister is a covered passageway typically with a colonnade open to a courtyard on one side. Such spaces are common in convents, monasteries, cathedrals or collages set in older structures. There is a unique relationship between the inside and outside parts, where one is sheltered yet connected intimately to the open space.

This is that architectural datum that guides the parti of the Cloister House designed by HYLA Architects. The square-shaped plot allows for the exploration of such a planning. The client is a professional who lives here with his aged parents, and gave a compact programmatic brief asking for three bedrooms and a guestroom alongside a living area, dining area and kitchen.

Fengshui requirements also helped form the architecture. It required two bedrooms to be on the first storey and the rest to be housed in a tower. “With two of the three bedrooms located on the first storey, the challenge was how to separate the living areas from the private rooms. The solution was to invert the relationship, with the public spaces facing internal courtyards and the bedrooms facing the front garden,” says Han Loke Kwang, founder of the architecture firm.

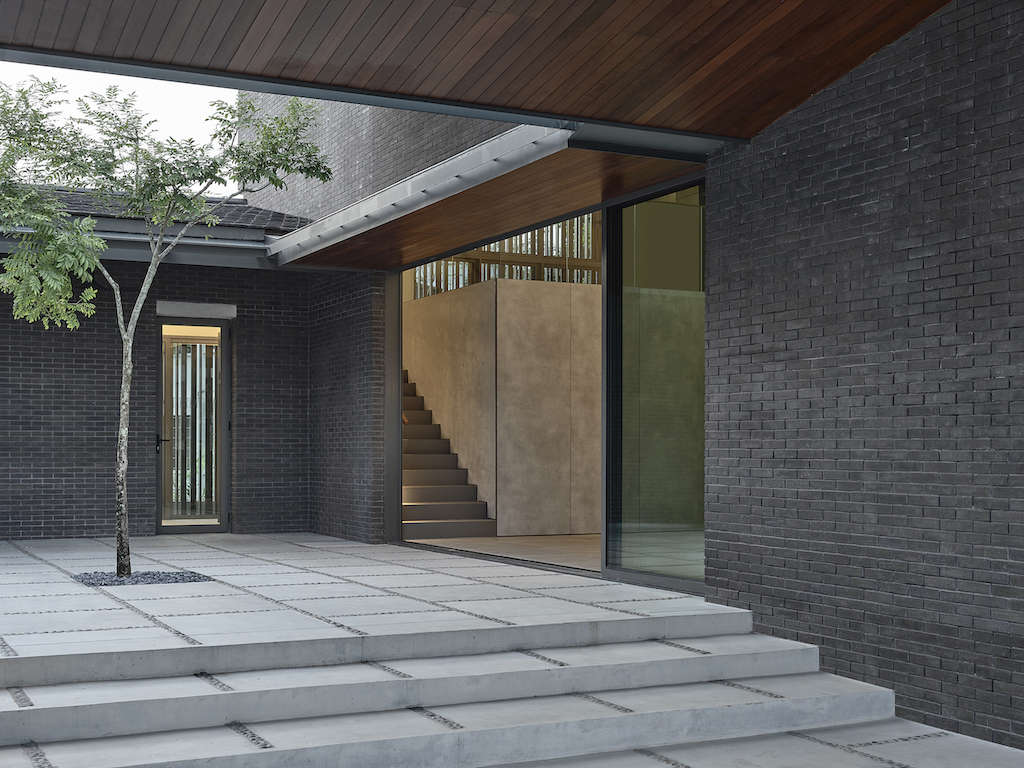

The ‘tower’ sits on a squarish base punctuated with a courtyard in the centre. “The feeling is like that of a cloister. It is private and meditative,” Han describes of this enclosed space. The planning shapes an intimate connection with the outdoors throughout the house, allowing ample pockets of breathing space both visually and physically.

There is another courtyard that one encounters upon approach at the driveway. It houses shelter for parking and direct access to the serviced zone. This leads into the dining area and dry kitchen, lined on both sides by glass sliding doors. One faces the driveway and the other, the internal courtyard.

The client and his mother’s bedrooms are on the first storey, stitched into a loop around the internal courtyard. The idea of ground-floor living is a rare on in Singapore’s tight plots, or in conventional briefs that prefer to bolster the first storey with social spaces and tuck the private spaces above. In this case, the occupants enjoy unencumbered connection to the land – be it whether together or alone in their private chambers.

The mother’s bedroom has a small glass door to enjoy the light and feeling of space from the courtyard. The third side of the courtyard contains the corridor linking these two spaces, while the fourth is the client’s bedroom. Bands of windows in the latter spaces connect them to the courtyard. In another twist, the client’s bedroom fronts the house, facing a generous garden. A layer of screens provides security and sun shading.

In the tower block, each floor contains only one programme – dining room on the first, the living area on a mezzanine, the father’s bedroom on the second floor and a multi-purpose room at the attic. Both bedrooms above enjoy some form of outdoor space – a balcony wrapped with aluminium screens for the father, and a pebble garden in the attic, lit with ample light from the open sky.

The house’s minimal materiality gives the architecture a monolithic quality. Precast concrete slabs and pebbles for the external flooring, including the courtyard, provides a tactual experience as one traverse about. There are pewter-toned homogenous floor tiles at the kitchen and several off-form concrete walls.

These various shades of grey complement the dominant use of face brick in an ashen shade for the architecture and provides a tranquil backdrop for everyday domestic routines.

“The idea is for the space to be architectural and not let the materials come in the way, so we use concrete and face brick in the most pure manner. Not many homeowners in Singapore can accept these kinds of materials and pared-back aesthetic, but it is perfect for this house,” architect Nicholas Gomes observes. Clay tiles are used for the roof, their tactility palpable as the roof hangs low at the low-scaled courtyards. Timber-lined ceilings accentuate the roof pitch that slopes upward at the front of the house and dips low into the courtyard.

By way of courtyards and other strategically placed openings and screens, the house was designed to coexist with the climate rather than against it. Deep overhangs and the sliding aluminium screens aid in giving thermal comfort. Says Gomes, “The control of heat whilst letting in light is key to designing sustainably in the tropics. It was great to have clients that conveyed an intent to live comfortably without the use of air conditioning.”

He adds, “The interiors of the tower block are shielded through a blank, double-cavity facebrick façade and verandah, with the courtyards enabling cross-ventilation to further dissipate heat. At the top of the stairwell, a roof ventilator passively expels rising hot air.”

The Cloister House reaches a new chapter in the firm’s evolving discourse on the courtyard typology to create tropically attuned abodes. “In terms of house design in Singapore, I would say this mainly single-storey structure-and-tower [combination] is quite unique,” says Gomes. “It’s the prefect site and perfect brief to do something like this, and also appropriate for the climate.”

Share

Share