The discussion on sustainable architecture is well fuelled by the advancement in technology. But the essentials of good buildings remain simple, albeit overlooked at times – well-thought out details, functioning spaces, climatic suitability and delight. Vitruvius’ dictates of ‘firmitas, utilitas and venustas’ (strength, utility and beauty) serve as a good guide.

In House of a Thousand Leaves by Zivy Architects, these are found to be present. The owners are an elderly couple that built the house hoping that their grown children will move in after marriage. At three-and-a-half storeys, the rebuild rises taller than its neighbours. But it maintains a light demeanour due to a concrete screen that divides the main spaces from the party wall at one side; it stretches up the full height of the front elevation, continues at the roof as a skylight before folding downwards at the rear as another screen, mimicking the front façade.

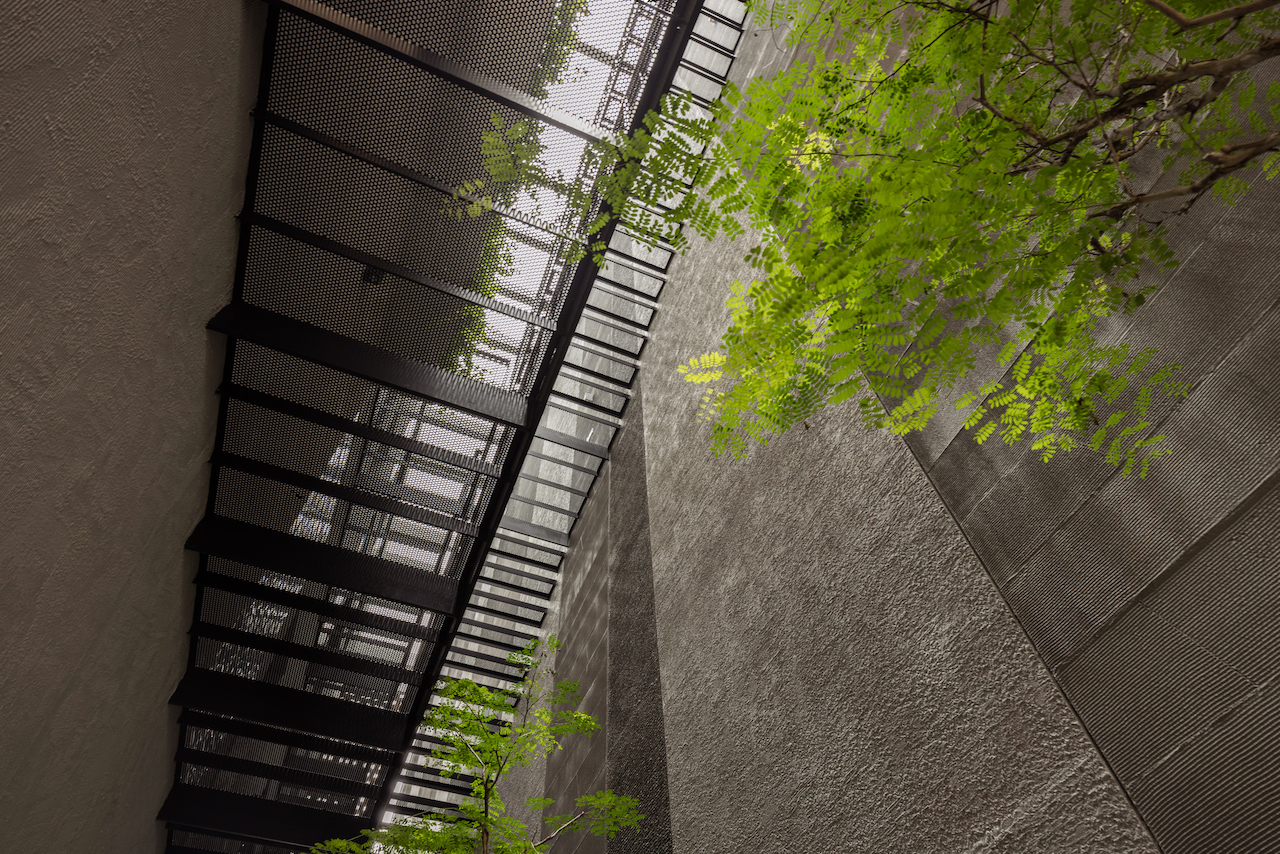

In this way, the narrow and long plot that measures 9 by 38 metres received plentiful light inside. Airflow through the north-south layout is also good, and the uninterrupted vertical volume beneath the skylight mitigates the plot’s narrowness. The staircase rising up the atrium deploys perforated stainless steel treads to enhance light and airflow. On the first storey, a planter runs the length of the house. One walks on stone pavers, their gaps filled with pebblewash along this corridor that blurs perception of the indoors and outdoors.

Back to nature

“The homeowners have a deep love for gardening,” says Loh Zixu, who founded the firm with his wife, Evy Sutjahjo and shares that the owners wanted the house to allow for them to comfortably pursue this passion. But first, the architects had to tackle challenging site situations. The house fronted a road junction, and other houses beyond. A concrete screen in front of the living area helps with that; a gap above letting in daylight and a small lotus pond bring some mood and relief.

“While the frontage may not be considered ‘ideal’, the house made up for it by being perched on high ground, with the rear sitting a full storey above the houses behind. This elevation gives the back of the house some of the best, uninterrupted views,” says Loh. He shares two key architectural intentions – to focus on maximising views and optimising the internal layout.

“The first major design move was to create an internal ‘view’ by introducing a quadruple-volume atrium. This atrium will serve as the heart of the home, acting as a breathing, garden-filled space that connects all the stacked levels. It provides shared, internalised views across the different storeys, giving the house a distinct sense of openness,” he adds.

Space out

The rooms, aligned on the other side of the plot, all have large sliding doors or windows looking into this void. The first storey spaces - a small sitting area and dining, the kitchen, powder room and the master bedroom - opens to the stone walkway that runs parallel to the linear garden. Hence, exiting from these rooms feel like walking directly into a shaded garden.

The second storey is reserved for one son, and the third storey is reserved for the other, although a front room on this level is currently a gym. Sutjahjo shares that the second key strategy was to take advantage of the rear views. They thus oriented the sons’ bedrooms at the rear. In the attic, a small terrace was also positioned toward the panorama. Between this and a utility space tucked away from sight but still receiving ample daylight for drying clothes, the owner’s tearoom is another gathering space.

On the house’s materiality featuring many raw surfaces, Sutjahjo explains, “It was a natural extension of the design vision to create an outdoor-inspired spatial experience. Some materials, like the textured paint on the atrium wall, bring a bold, tactile quality; various levels of roughness and textures were explored to achieve a carefree, unique aesthetic.” These contrasts with smooth, ‘quieter’ materials, such as the micro cement flooring at the attic tearoom embedded with walnut timber chips that were repurposed from construction cut-offs.

Family bonding

For the architects, this house allowed for much discourse. “In Singapore where land scarcity, and rising housing and construction costs pose significant challenges, the idea of living in close proximity to parents and siblings deserves further exploration. The multi-generational house typology can foster a renewed sense of connection among different family units, if degrees of privacy can be balanced and negotiated via design,” says Loh. Testament to the design, the sons now live with their parents and their wives in this house.

Throughout, communality is allowed for but not enforced. For example, the staircase in the atrium is a theatre to the coming-and-goings of family members; placed at the entrance, it means one can head upstairs without having to go through a specific zone. The porosity also means the air-conditioner – and even the fan – is rarely used. Reflects Sutjahjo, “The house serves as a great example of how a tropical home can embrace a modern aesthetic. Beyond that, it shows that sustainability isn’t just a theory, but a mindset integrated into every step of the process.”

Share

Share