Gregorio and I are discussing the Tri Hita Karana, a concept held by Balinese society that encourages one to always be in harmony with god, humans and the environment. This can be felt profoundly amongst the Balinese, deeply generous hosts who graciously offered travellers and settlers not only their island, but its spirits and indeed themselves.

In the beginning this generous gift was gratefully acknowledged and deep connections were made between foreigners and natives. However, at some point, not so long ago, a new wave of less couth visitors have descended upon this paradise, creating ruptures.

‘This is bigger than Taman Bebek’, Gregorio and I mull this over with equal amounts of excitement and trepidation as we sit by an enchanting, jungle-tickled swimming pool that may soon be nothing more than a muddy crater.

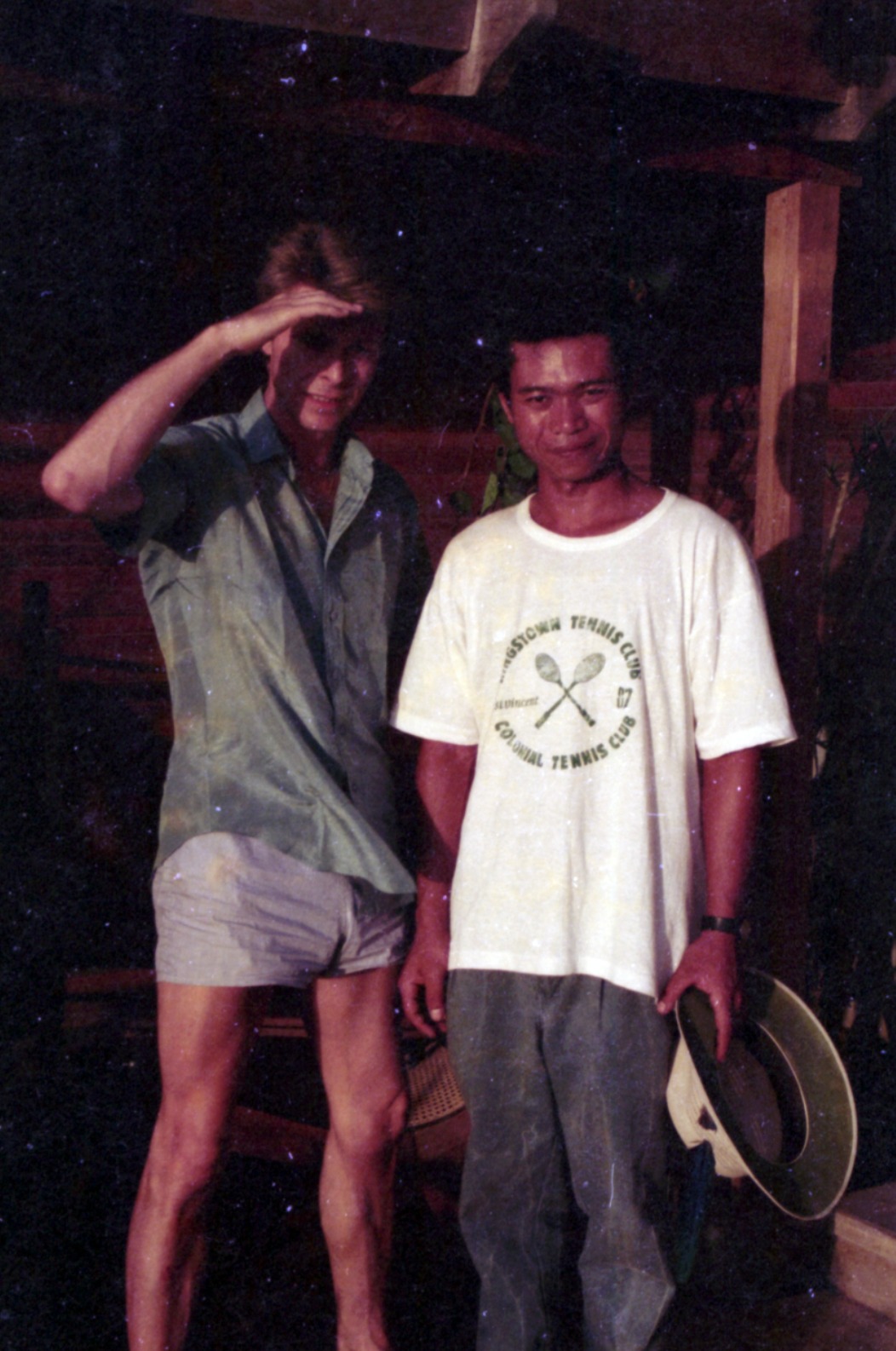

Gregorio and Rita von Hildebrand, intrepid travellers, documentary filmmakers, textile collectors and accidental hotel owners, are finding themselves in the midst of a story that truly beggars belief, but which also has the potential to transform from a personal plight into an island-wide crusade to slam on the brakes of ‘the wrong kind of’ change.

A substantial portion of legendary estate Taman Bebek, an exceptionally unique vernacular boutique hotel in Ubud, which the von Hildebrands have owned and managed for the last eight years after its previous owner Made Wijaya passed away, is facing imminent demolition.

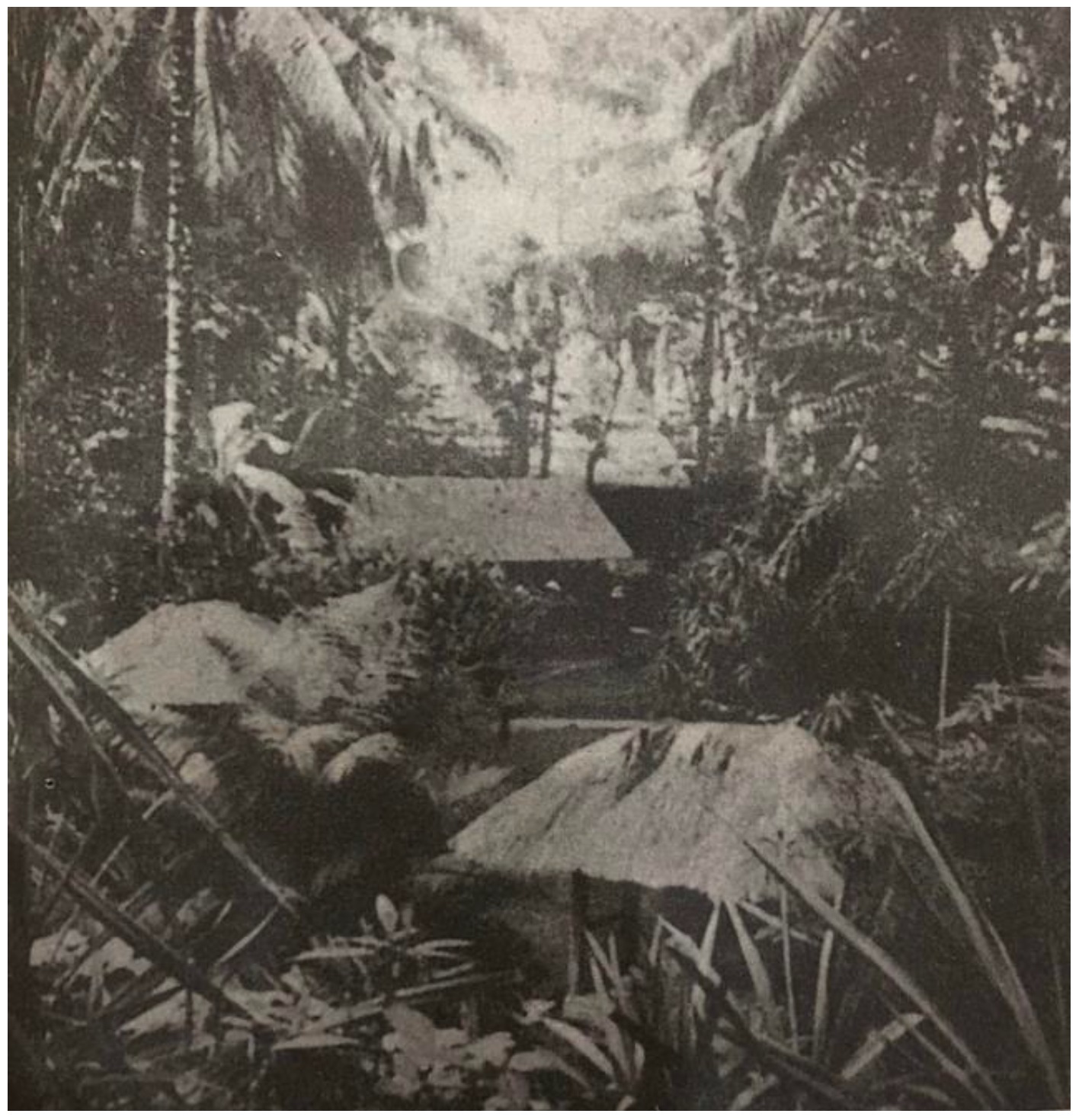

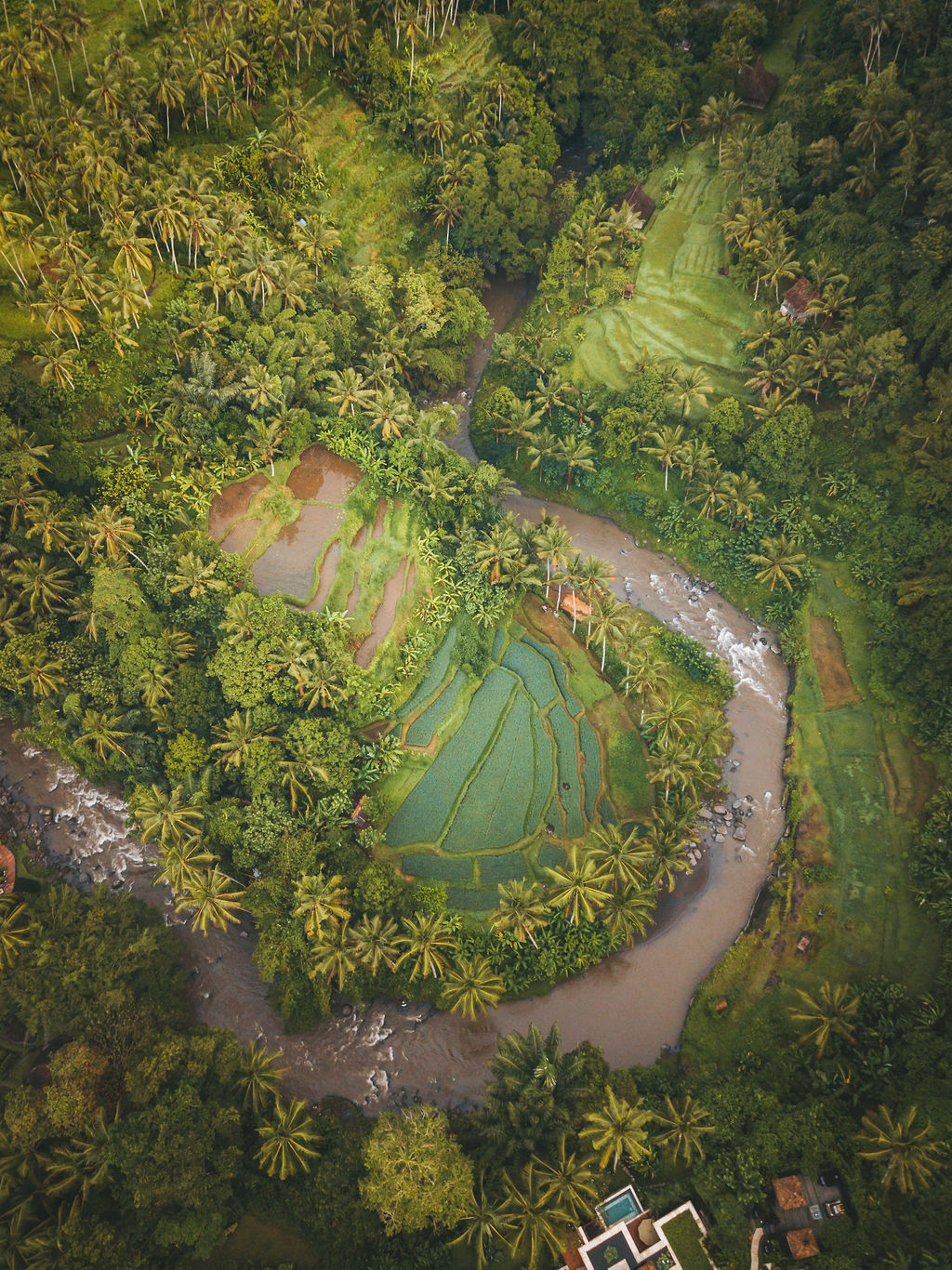

Taman Bebek’s wonderful story began in the 1930s when American ethno-musicologist Collin McPhee, and his anthropologist wife Jane Belo, with the help of German artist Walter Spies, built a small Balinese enclave on The Ridge, as the location is lovingly called, directly above the centre of the magnificent croissant-shaped Ayung River and the glorious lush valley it slithers within. Influential academics soon joined them, extensively studying, researching and penning numerous books and texts about Balinese culture (McPhee’s A House in Bali is considered essential reading), immersing themselves into local life and working directly with enthusiastic native mentors. The collaborations and searches for higher aesthetics that took place during that time caused tectonic shifts in the world-view towards the island, and helped put Bali on the global map.

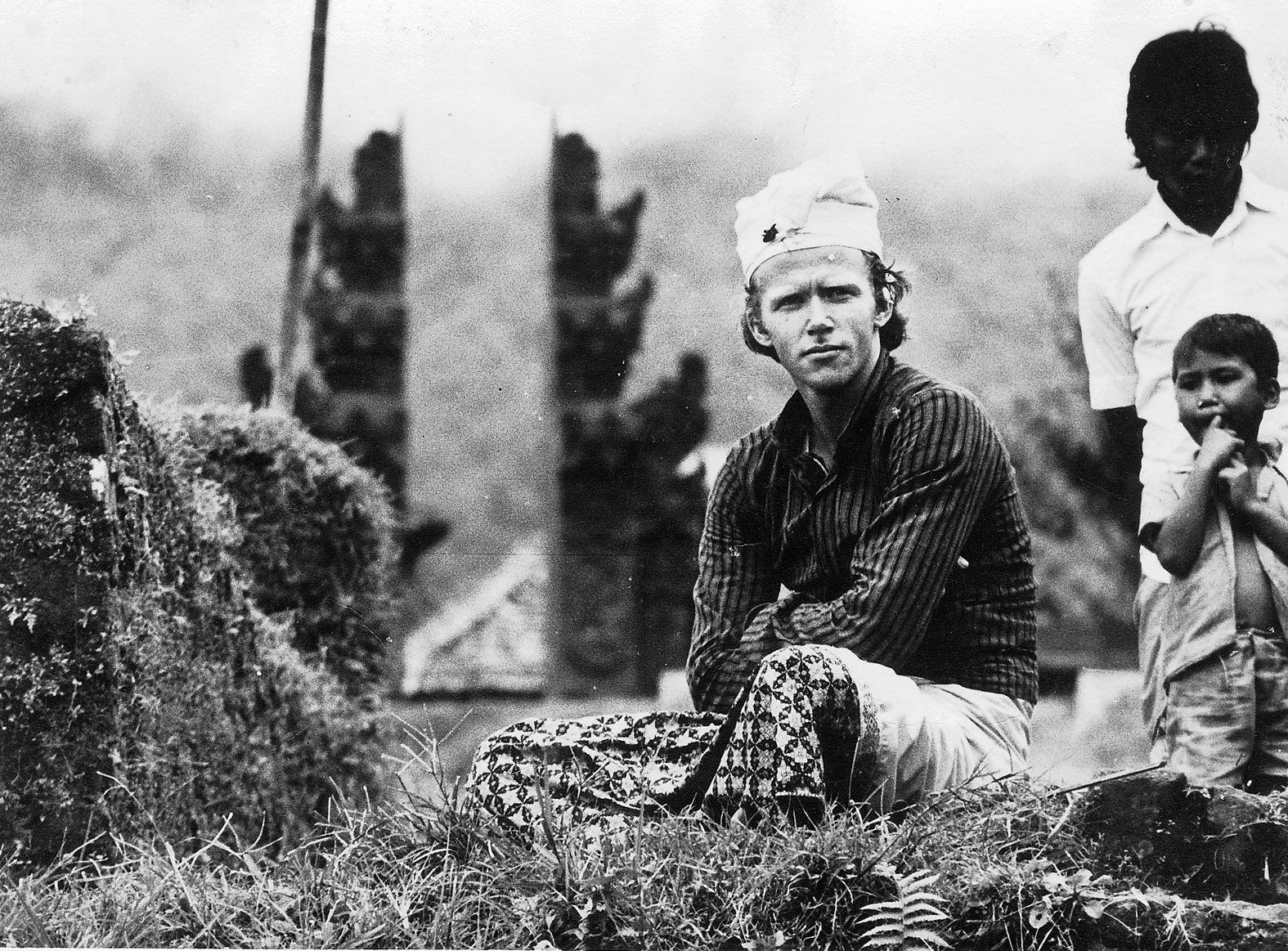

After WWII Taman Bebek fell victim to the jungle until Bali-settler Made Wijaya (born Michael White from Australia) acquired the land in the late 1970’s and faithfully re-constructed the original pavilions and cottages. He wove his magic in the gardens too (he called himself the world’s ‘last poetic gardener’) and went on to become the foremost global authority on tropical and Balinese landscape gardening, very much a legend in his own right.

Soon this combination of the estate’s rich history, Wijaya’s ridiculous talent for taming the fecundity of nature, and his own magnetic gregariousness, made him the world’s first super-host. He brought together a plethora of luminaries, rockstars and ambassadors who came to the newly re-opened island after its own political and societal challenges had simmered down. David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Yoko Ono and Francis Ford Coppola, to name a few, rubbed shoulders here with orchestras of crickets and frogs providing the musical scores for many spirited discussions and parties.

Taman Bebek was a veritable beehive of Bali-enthusiasts for over 90 years and, walking around it with Gregorio, utterly awe-struck by the truly biblical view, it still feels like that original springboard for accessing and understanding what the first voyagers to Bali in the 18th Century pronounced the ‘literal’ Garden of Eden.

The compound is made up of stitched-together parcels of land, owned and leased out by different landlords, and the plot in question is none other than the one bearing Made Wijaya’s and Colin McPhee’s modest villas, the two men who have been the very heart and soul of it since its humble beginnings.

Due to a cacophony of unfortunate circumstances, including the complexities of land ownership and ambitious brokers, a seeming absence of mechanisms to protect historically important buildings, and a foreign buyer’s complete lack of sensibility towards the value of preservation, the land was sold behind the von Hildebrand’s back and they have been trying to save it ever since.

Gregorio has coined this misdeed ‘Another Sacrifice to the Gods of Capitalism’ and, as we marvel at the spectacular sunset lava-lamping on his familiar horizon, he quips nervously that “perhaps this is the last time I will be able to recount the rich history of Taman Bebek at Taman Bebek itself”.

But there is so very much more than just their business at stake. There is the legacy.

Many consider it a legacy property like no other in Bali, but it now has a mighty nemesis. His sights are solely on the, arguably, ‘best view on Bali’ but even the awkwardness of an entire community disagreeing with his actions is no deterrent.

Gregorio has been attempting to alter this trajectory by rallying together signatories on a petition (with over one thousand signatures from the Who’s Who of Bali already, and counting) which he is hoping will come to be the proverbial butterfly wings that cause a storm of reform. Which seeds of change its raindrops will fertilize, however, remains to be seen.

This is not the first time a ‘heritage’ property on Bali has faced this detriment and it will likely not be the last. Bali’s borders, like its surf waves, are swelling with investors, developers and opportunists who just want a piece of it.

Gregorio elaborates: “Today’s incoming investors are simply doing what they want, taking advantage of scenic backdrops and high ROI’s without any interest in context, culture or history. Pandemic-bruised land-owners don’t want to lose an opportunity to sell at prices never seen before and so cultural places and entire neighbourhoods are being sacrificed and transformed into a new Bali, one that looks less like the one people fell in love with and more like the rest of the world. But there is no place like Bali, it’s irreplaceable”

To the Dutch orientalists of the early 20th Century Bali was a ‘living museum’. Many religious, sacred and archaeological monuments are being protected but this ideal is seemingly not upheld for early gathering places of study, equally as important to the island’s anthropological, heterogeneous, vernacular and cultural narrative.

‘Tourism relies on culture, but tourism is a threat to culture’ wrote French anthropologist Michel Picard in 1991. He described the worrying dynamics of a host society, in this case Bali, as being ‘hit by a missile, like an inert object, passively subjected to exogenous factors of change with the subsequent problem of assessing the ensuing fallout’. His predictions grow ever more accurate with every passing day on the Island of the Gods, so named in the 1920’s, ironically by foreign visitors.

Of course many Balinese care very deeply about their history but with the island becoming increasingly overrun, in-demand and more expensive, there is money to be made and families to feed.

Because legacies do not simply evaporate, why then also the need to save a bunch of old buildings? There is of course nostalgia, architecture and craftsmanship, artistry and old-world aesthetics, the smells and sounds of the past and the echoes of its pioneering former inhabitants’ voices still bouncing off their walls.

Structures are the tangible cultural heritage we have.

However, there is something far more consequential that needs to be saved at this very poignant point in Bali’s history – the lives that were lived at Taman Bebek were consciously adhering to the Tri Hita Karana, a harmony that is wobbly at best these days. This is what must be preserved; this time capsule of respect and absolute connection to the true spirit of Bali.

Gregorio touches on a fundamental point: “In the beginning there was a ‘good host/good visitor’ dynamic here. Bali has always been an exceptional host and people came here to find inspiration and a certain freedom. There was so much to gain from crossing that bridge of relationships…it was a multi-dimensional one that informed, and reflected on, architecture, daily life, literature, film, the list goes on…but this is now teetering on the edge of being lost”

So as the Sword of Damocles hangs over Taman Bebek we wonder whether the tsunami of support, that the threat to this icon has triggered, will transform into a great success story, perhaps too late for Taman Bebek, but it could become the fodder needed to fuel the fires of change before others face a similar fate.

I ask Gregorio whether he has it in him to fight the bigger fight: “I don’t want a legal fight. Taman Bebek is a symbol of good hosts and good visitors, it is a beacon of generous hospitality, 95 years of that. There are hundreds of signatories on the petition who disagree with its destruction and the question now is whether we can come together and form an association or foundation for the preservation of properties of cultural and historical relevance. Can we do that here in Bali? This is the bigger story”.

Taman Bebek was master-minded for reflection, learning and decompressing from the rest of the world but this Bali, which was once the escape and retreat from the hustle and bustle of a modern world has now itself become commotion and hubbub as any scooter-horn-riddled-exhaust-fumed-ride on its streets demonstrates.

The original gamelan that McPhee presented to the outside world in the 1930’s is still played, unbeknownst to its listeners, at the Four Seasons Hotel in Sayan which overlooks the same valley, but this instrument alone is not capable of telling and re-telling the stories of its original discoverer.

Sometimes it takes a village. In this case an estate.

The loss of Taman Bebek will chip away at ever more of Bali’s rich history but the winds of change are definitely in the balmy night air.

Ms Hauger pursued this story on her own accord without material or financial support from the Publisher.

Share

Share