Piet Mondrian is no stranger to the De Stijl art movement. His most prominent works consist of lines and an overlay of primary colours that, until today, serve as inspirations to fashion houses and artistes all around the world. His ventures from Netherlands to Paris, then London and finally New York, where he remained until his death, witnessed some of his greatest influences in arts and design, fashion, architecture and cultural references. From Yves Saint Laurent’s Fall 1965 Mondrian collection to the 17-storey Parc Mondrian in Singapore, Mondrian has a unique allure that captivates an instant commanding attention.

In commemoration to Mondrian’s prominent contributions towards the arts, as well as the 100th anniversary of the De Stijl art movement, Dutch design studio Tinker imagineers traces the life of the painter from his birthplace – Netherlands – to New York where he was laid to perpetual rest.

There are four relevant ‘Mondrian spots’ in the Netherlands: Winterswijk, where he spent his childhood; Otterlo and The Hague, where Museum Kröller Muller and the Gemeentemuseum have the largest and most important Mondrian collections in the world; and Amersfoort, where he was born. The first three present work from every phase of the artist’s life, and are eminently placed to illustrate the artistic aspects of his story - which they do with gusto. This presented Amersfoort with the opportunity to focus on Mondrian’s life. And so, the Mondriaanhuis decided against a museum-like set-up, but rather to tell his story with the use of multimedia: modern, interactive, inclusive, and one of its kind. The leitmotiv in the concept development and production of the video installations was to tell Mondrian’s life story without words to a mixed audience.

In March 2017, the renovated Mondriaanhuis (phase 1) opened its doors to a new audience of culture lovers, tourists, children, and young people. The curators brought Mondrian’s birthplace to life, and guide visitors along the cradles of his art by means of a new interior and two innovative video installations.

To quote Mondrian’s motto in life, “Don’t adapt, create!”, the assignment was for the museum to tell Mondrian’s life story in a new way, suitable for a broad and international audience. Piet Mondrian’s formation is the silver thread running through it all. The child, the pupil, the idealist, and, after a remarkable turn by the end of his career, the master. Visitors take a trip along the places where his work was conceived.

“Most people are mainly familiar with his abstract work, and we wanted to show that his range was much broader. In addition to the interior design concept, we created two video installations,” shares the organisers.

The big idea was based on the concept of an empty canvas. When entering the Mondriaanhuis, you experience a white, bright space. Along the route through the museum, the canvas of his life is gradually filled in with stories, his thoughts, his space. The artistic signposts consist of large, coloured areas that refer to colours from his entire oeuvre, such as the dark greens or pinks from his early period. These have been hand painted in the layered structure that is characteristic of Mondrian.

The ‘screens’ of the video installations are empty canvases as well. A frame with black-rimmed, rectangular planes for the Works installation, and a transparent cube for the New York installation. Video-mapping is used to project the picture stories on these extraordinary canvases. A deliberate decision was made to use a universally understandable audio-visual language, without resorting to text or voice-overs.

Before long, work on the Mondriaanhuis will continue with, among other things, a trip along the highlights of his Dutch period, an upgrade of the Parisian studio and DIY studio, and an intermezzo in London.

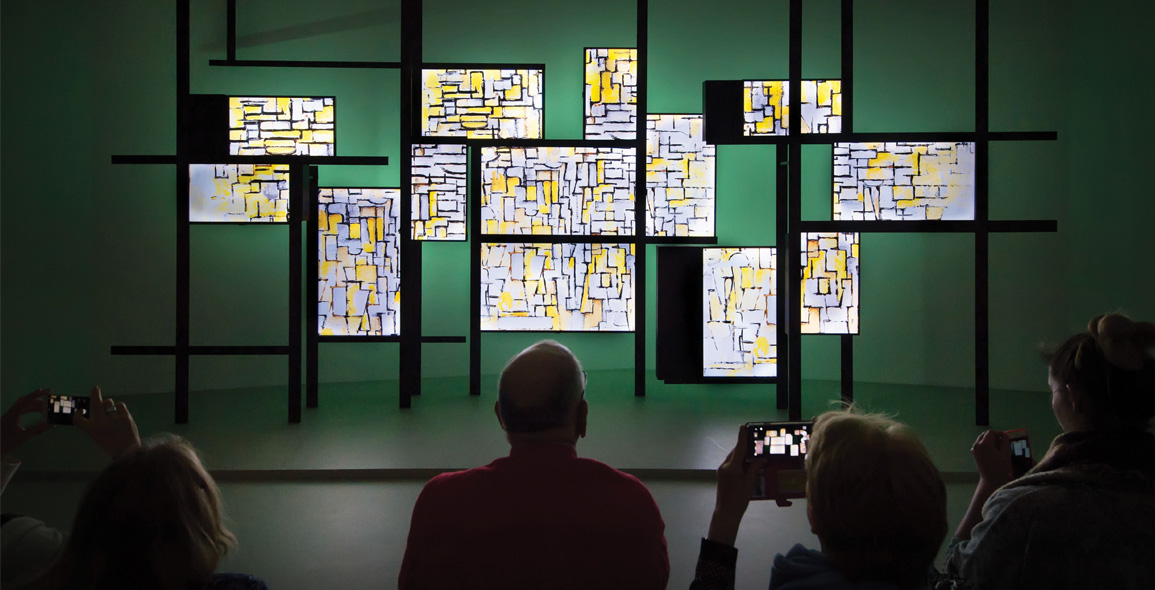

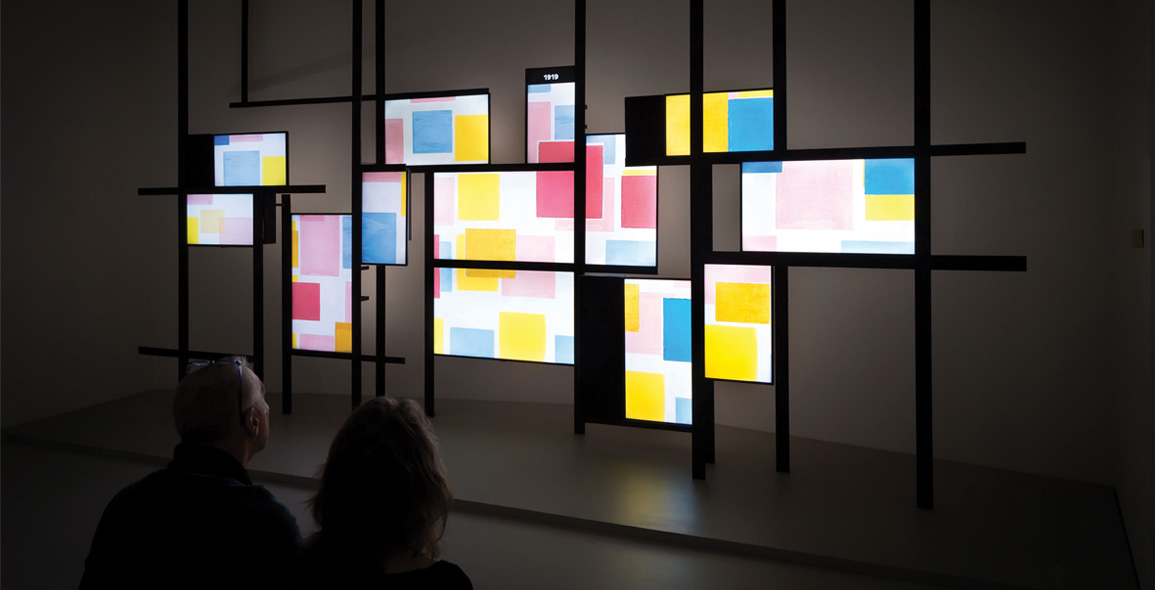

The Works

Mondrian’s paintings, presented one after the other as a musical picture story, make for a compelling start of the visit.

In a five-minute show, visitors witness the painter’s artistic development, from realist landscapes via ‘luminist’ scenes to his abstract compositions with their distinctive lines and planes.

The audience is seated in a small theatre, with room for circa 45 people. The frame (the carrier) is the empty white canvas, made up of black-rimmed planes that refer to the layered structure of his abstract work. The Works presents an extensive selection of his paintings, in chronological order and at a high resolution. One after the other or alongside the other, the showcase makes full use of the 13 available screens.

Sometimes the camera zooms in, while we follow Mondrian in his search. Longer lines of development are alternated with small revolutions. By watching the presentation, the connections become clear: the variation of the 1910s and the concentration of his later years. The contemporary music that Mondrian liked, from Ravel to jazz, from Stravinsky to boogie-woogie, accompanies and underlines the story on the screen. “The music collage is ever changing, in keeping with the chronology one passes through a world of form, climbing from the real to the abstract.” [Mondrian]

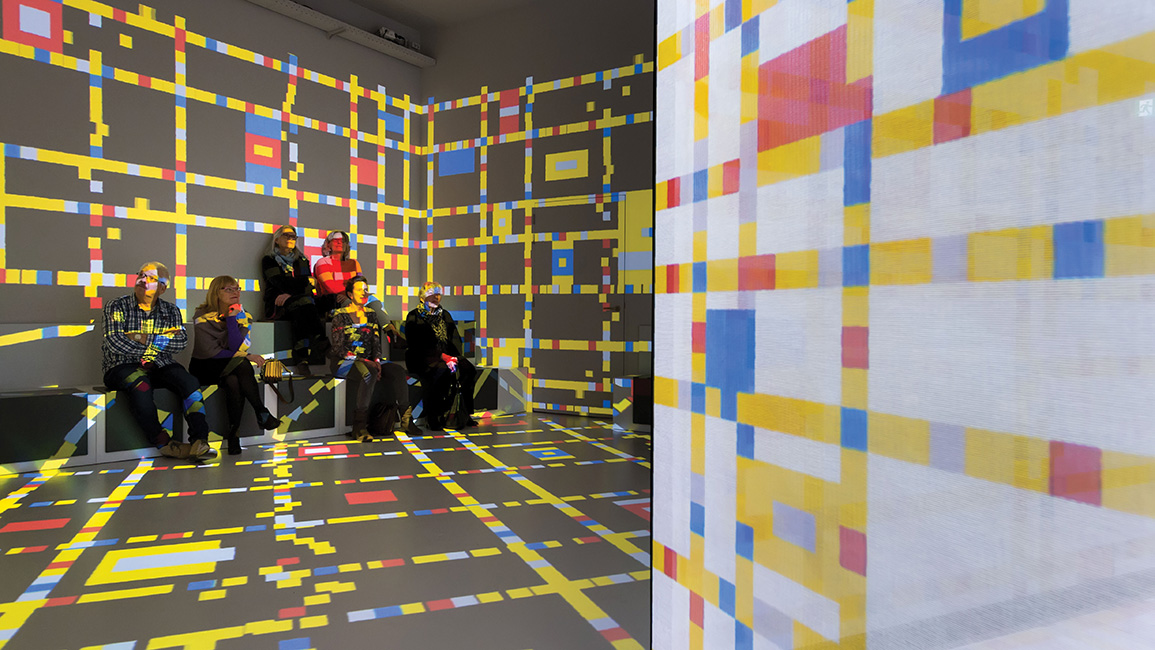

New York

New York city life and Mondrian’s late work – boogie-woogie, clear lines, yellow, dynamic planes, and his favourite music – intertwine into one immersive audio-visual spectacle.

In New York, Mondrian, the master, starts afresh. He gets rid of the black lines and explores new spaces in his work. He discovers that lines are planes in themselves. He reinvents himself, focuses on movement. The American influence becomes clearer: boogie-woogie music, Disney films, the city that never sleeps. Everything he has created up until this point comes together. His Victory Boogie Woogie is never finished.

Visitors are immersed and involved in the artistic quest from Mondrian’s New York period. Mondrian went through a theosophical evolution, from reality, via dreams to spiritualisation.

Tinker imagineers concludes: “We put visitors in a dreamlike state, to allow them to follow in his footsteps. It’s not like they ‘become’ Mondrian, but rather that they get to visit his dreams. They look in on those dreams and see flashes from the world outside: brief, distorted, and subjective.”

A print version of this article was originally published in d+a issue 98.

Share

Share