Anees Maani was born in Amman in 1973, and was introduced to sculpture in Russia in the early nineties, when he ‘tried’ to study architecture when fate serendipitously intervened and moulded him into a sculptor instead. Anees went home to Jordan and secured a two-year apprenticeship with renowned sculptor Nazih Owais.

His most recent solo, his sixth, was recently held at Galeri Chandan in Kuala Lumpur, and this wonderful conversation ensued.

What are the sources of your inspiration, and which artists have made an impact in your artistic life?

My work is mostly about the evolution of forms in nature and in human culture; most of my sculptures are inspired by basic forms, natural or created by many cultures in different environments throughout history. I have been inspired by abstract works of Matisse and Brancusi, as well as my Jordanian teachers Nazih Owais and Samer Tabbaa. Many other artists inspire me all the time, so I try to keep following what is being created and I try to stay open to be inspired and influenced by all good contemporary art.

Did your childhood influence your work?

I am one of twelve siblings. Almost everyone in my family including my parents are into art. The creative environment demystified the process of making artwork. This encouraged me to try the adventure.

What is the advantage of creating sculptures? Why are you so passionate about it?

The moment I started sculpting, I could not stop. I find it a great way to explore life and enjoy it. My eyes are constantly looking for textures and forms, and learning is an endless process that keeps me curious and happy. I hope other people can also experience joy when interacting with my sculptures.

What is your current project, and what are your strategies for the future?

I have been living in Jordan where I was working on the evolution of forms. Now I’m trying to concentrate on one or two aspects of that research. I’m leaning towards forms I see in the jungle. I am also trying to learn more about wood from the rich Malaysian wood culture, so I’m mostly working with wood now, trying larger and larger pieces. I hope to continue making sculptures, traveling, learning and exhibiting around the world.

What difficulties do you face in constructing and displaying your work?

Exhibiting is always a challenge, especially having a solo exhibition. Booking a gallery is not easy. Then comes the production of the sculptures, which involves a lot of mental and physical work. Then the logistics. But it is all worth it when I see people enjoying my work.

What are your favourite sculptures you have finished?

Every now and then, my favourite sculpture changes. Sometimes it is one of the newer ones but often, some of the good old ones comes back to take its place as my favourite. Some of my preferences from different times became my own private collection.

What does your regular day entail? What do you like doing when you are not making sculptures?

Whatever I’m doing, I would always be thinking about art and sculpture. The process never stops. I like spending time in nature, archaeological sites and art and archaeological museums. Some of my days are studio days, early, and fresh. I start my chainsaw and begin the fun.

What would be the epitome of a sculptor’s studio?

An ideal sculpture studio would be big, with machines that can help lift and move heavy pieces of stone or wood. And the studio would be located where the sounds of my tools would not bother people who are nearby.

Could you tell us some exciting details about your life?

I have worked as a mountaineering guide in Jordan. I have also worked on several movie productions as a props maker, and even an art director, with American and local Jordanian productions.

Share with the readers about your latest show at Chandan, Lines.

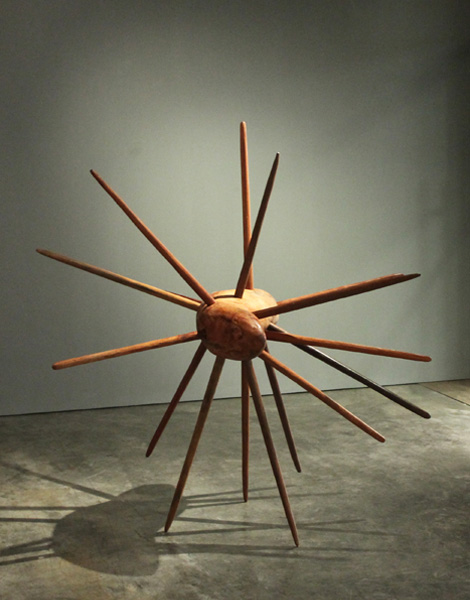

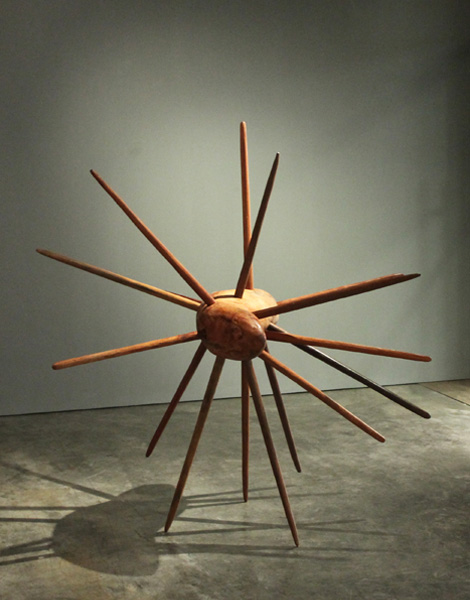

Lines is my sixth solo exhibition. I exhibited ten wood sculptures and three aluminum ones. It had a sample of recent sculptures where lines started to become a part of my sculptures, something I think I picked up from observing plants and insects in the jungle. I was excited to show these sculptures and get feedback from visitors to the exhibition.

How do you perceive and comprehend public space and the part of art in public space?

Public space is as an essential element in the structure of any community. Placing artwork in public is refreshing and educating; it encourages people to try diverse views and become more accepting of the other.

Do you observe a certain connection between nature and your work?

Yes, sure, I am always fascinated by forms, how they happen, what materials and environments with certain factors could change a form into another; nature is full of forms that took millions of years to evolve, and that is an endless library for me to study.

Looking at Anees’s works, one gets a sense of the dense and void, of time and space, of heaviness and buoyancy. Artist and Curator Benedetta Segala observed, “Anees illustrates, through his art, the dichotomy of the human experience of time, between repetition that can be problematic, and limitless innovation that can be chaotic. The artist has found a centre of balance between past and present, between archaism and modernism, reaching that universality worthy of being called art”.

But what engages most is the artist’s quirky style, which at times resists labelling. It is that palpable tension between the internal and external space that is beguiling: some of his more potent pieces are his seriously chunky pieces, of blunt shards which resemble some sort of an ant and spider hybrid, the unadorned square frame containing an invisible mirror, all beautifully-peculiar and curious. There is a reason why most of his works remain untitled; we are supposed to ‘decipher’ them, these extraordinarily-stark works which dares you to refamiliarise yourself with the very things which you think you know about.

But don't.

A print version of this article was originally published in d+a issue 99.

Share

Share