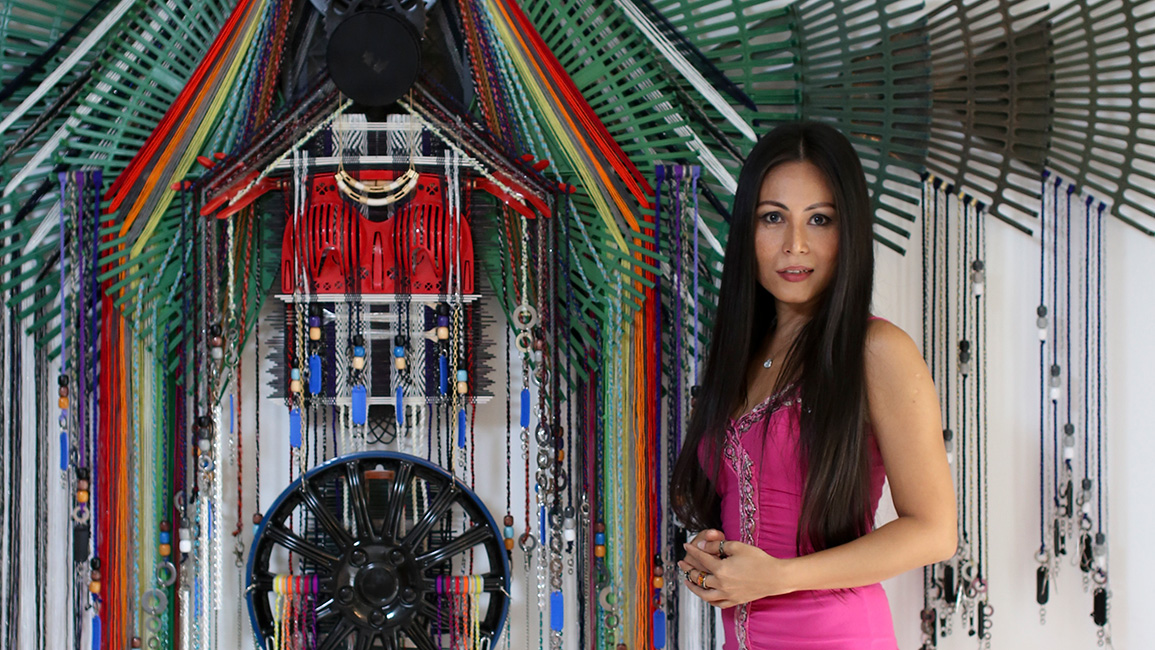

If a single-word choice is tasked to describe Anne Samat’s work, it would be an expression which does not sound even vaguely English: pulchritudinous. It is actually a fancy word for ‘beautiful’. But to sum up the artist’s tapestries as merely beautiful is doing her a great injustice. Unforgivable. And so pulchritudinous should be more appropiately described as 'heartbreaking and breathtaking beauty.'

Anne Samat has been in the art industry for two decades, but only in recent years, her works have become increasingly visible. She graduated from Malaysia’s Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) in the nineties, and her graduation thesis works immediately caught the eye of renowned glassmaker and painter Raja Azhar of Artcase Gallery. He took her under his wing, and together they mounted several exhibitions. He taught her grit; he schooled her of the harsh realities of a life as an artist. She took it all in and bloomed, somewhat. But it wasn’t enough to sate her eternally-famished spirit. Anne wanted to do more, Local collectors at the time were unsure of what to make of her work. It was craft they said, not art. It was pretty, they mused, but it was not really art.

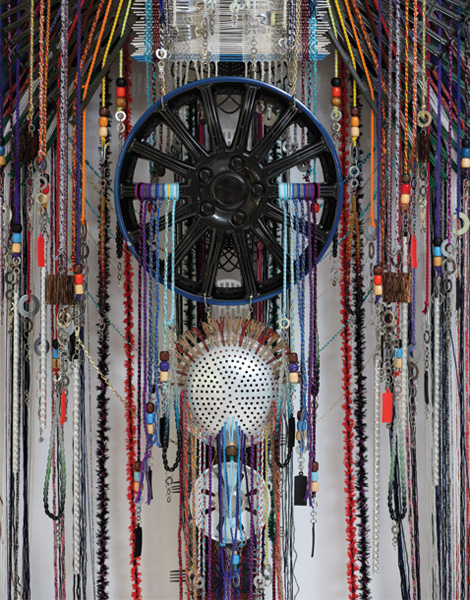

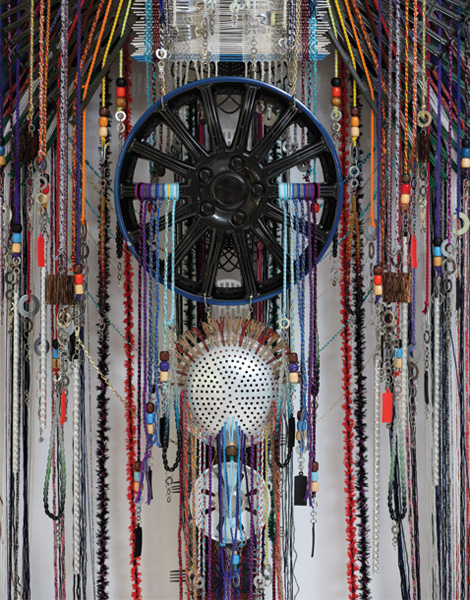

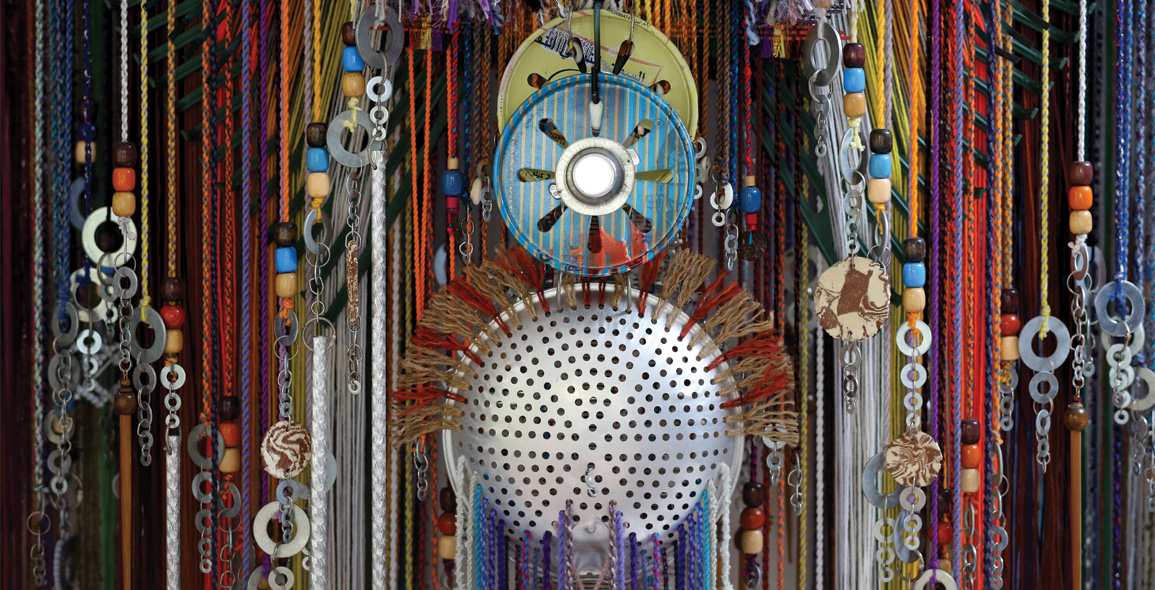

The artist herself is a fascinating creature; she had and has a wonderful touch, and a wondrous sense about art, and throughout the years, has never become a carbon copy of anyone else. She is a tough realist. “Right from the beginning, I wanted nothing more than to break this infuriating taboo on weaving. There is this perennial struggle, to create a seamless confluence between the feminine and the masculine in my works. I intentionally work with cultures and histories, and attempt to transform them with new and personal ones. Let me give you an example. I substitute the traditional Songket and Pua Kumbu with more contemporary materials. I use acrylic, polyester and rattan sticks instead of conventional silk, cotton, gold and silver threads. The results are pieces with unexpectedly bold layers and design. I make works which I fervently hope, translates as powerful yet gentle. I am a true believer in the immortal Malay saying, “Tanpa adat dan budaya, ibarat jasad tidak bernyawa – without culture, without custom, one is as good as dead.”

Strong words uttered by an equally strong spirit. Anne left for London in 1999 and continued making her art. She held small independent shows and returned home only to see her family. In 2014, I visited Malaysia’s National Art Gallery to look at their recent acquisitions, sauntered past most works, then halted, and back-tracked to this woven-assemblage of three freestanding effigies, a family of father, mother and child. It was unmistakably Anne Samat. I’d know her works even if they were dyed neon green, broken into a thousand parts and stuck to the ceiling.

I asked her the same questions when we had our first interview. She has matured tremendously, both in her works and as an individual, and that natural joie de vivre remains untainted.

You use a lot of unusual ‘found objects’ in your installations and tapestries. What do you find so appealing about the perception of things recycled as art? Does it have anything to do with socio-ecological questions and your reaction to them?

I use a lot of unusual objects because of one simple reason: they produce this almost ethereal quality and the work metamorphoses. It is all about undiscovered potential. A mosquito container becomes a face, garden rakes become ruptured ribcages, beads are veins, and hub caps are hairs. The possibilities are endless, ever evolving, and I am still dreaming of thousands more. And yes, socio-ecological issues are important; we must question our personal world-views, and our systems of beliefs. How else can change occur?

Which is more important in your work, the idea or the execution?

Personally, I see the importance and beauty in both, and a greater beauty in the journey that I take in order to complete the artworks. It’s not all about the destination; it’s about the journey, the process.

What kind of impression do you hope that your work has? Aside from the meaning, is it sufficient that your art just to be striking?

If people think that my artwork is beautiful, I hope they realise that beauty comes with a purpose. It is to encourage people to think ‘big’ and not be afraid to be themselves.

The greatest lesson in your profession was to never give up. Was there a time when you reflected on an alternative path? What feelings do you have when you look back at your life now?

Life is filled with trials and tribulations and that is the beauty of it all. I have once or twice thought about picking up another path. However I am glad that I have never thought about it in a serious manner. At the end of the day, I always believed that I was born an artist. I am in constant joy, fortunate and very grateful because my work is my hobby and my hobby is my career. Not everybody can make that statement!

Stepping Stone

With Richard, Anne has accomplished in less than a year what many artists would take five. At Art Stage Singapore this year, her works were an unquestionable hit. Her fabulous arrases were brought to Art Central Hong Kong in March, to New York in April, Volta, Basel Switzerland in June, the upcoming Yokohama Triennale in August, and we anticipate many more.

I asked if she still owns that fantastic loom. Anne’s face lights up. “My sacred loom-weapon of mass destruction? Yes, I still have it. I use it almost every day.” It was a gift from one of her former professors, and one she cherishes to this day.

Anne Samat has always possessed an oeuvre exquisitely-eccentric, her relentless quest to bring together, in perfect harmony, art and life is deeply admirable. We are reminded of curator Johannes Cladders' immortal words in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist’s in A Brief History of Curating. "That just because you put another label on the bottle, doesn’t mean the wine inside changes; it is the wine that needs to be altered. It is the inner attitude that needs to be altered. We have to concentrate on allowing art to evolve through how it is received.

A print version of this article was originally published in d+a issue 99.

Share

Share