It is quite the sight; you don’t really know what to make of it. But that is the beauty of Alex Seton’s works: a tad mad, wondrously-bizarre and deeply affecting.

The Singapore Biennale was in full swing, and part of the media itinerary was Seton’s Pygmalion. When you’ve written unfailingly about art (or any one subject for that matter) for so long, very little rivets anymore. The mouth asks typical questions to match typical works, and all you want to do afterwards is slink quietly back to the hotel room and watch Frasier re-runs.

Pygmalion changed that for a wonderful two hours. I was fortunate; Sydney Morning Herald’s outstanding art critic was with me. John McDonald, whose writings I devour, has written much about Alex’s works, and a quote of the artist’s entry for 2014 Adelaide Biennial, ‘Someone Died Trying to Have a Life Like Mine' which I memorised.

“..consists of a series of life-jackets carved from white marble, scattered across the floor. The reference is to 28 life-jackets that washed up on the shore of the Cocos Islands in May 2013. Instead of preserving life, these jackets would send the wearer to the bottom of the sea. The work is elegiac – as redolent of death as a field of tombstones. I can’t remember seeing an artwork that made so powerful a political gesture in such an understated manner.”

Thank you John, ever so much.

Pygmalion is just that: discreet yet screams with resonance. Much of Alex’s mechanisms stray from the customary, things which are way way way outside the normal strictures of the status quo. And his latest offering, Pygmalion, is a definite manifestation of unparalleled weird.

It stirs the blood.

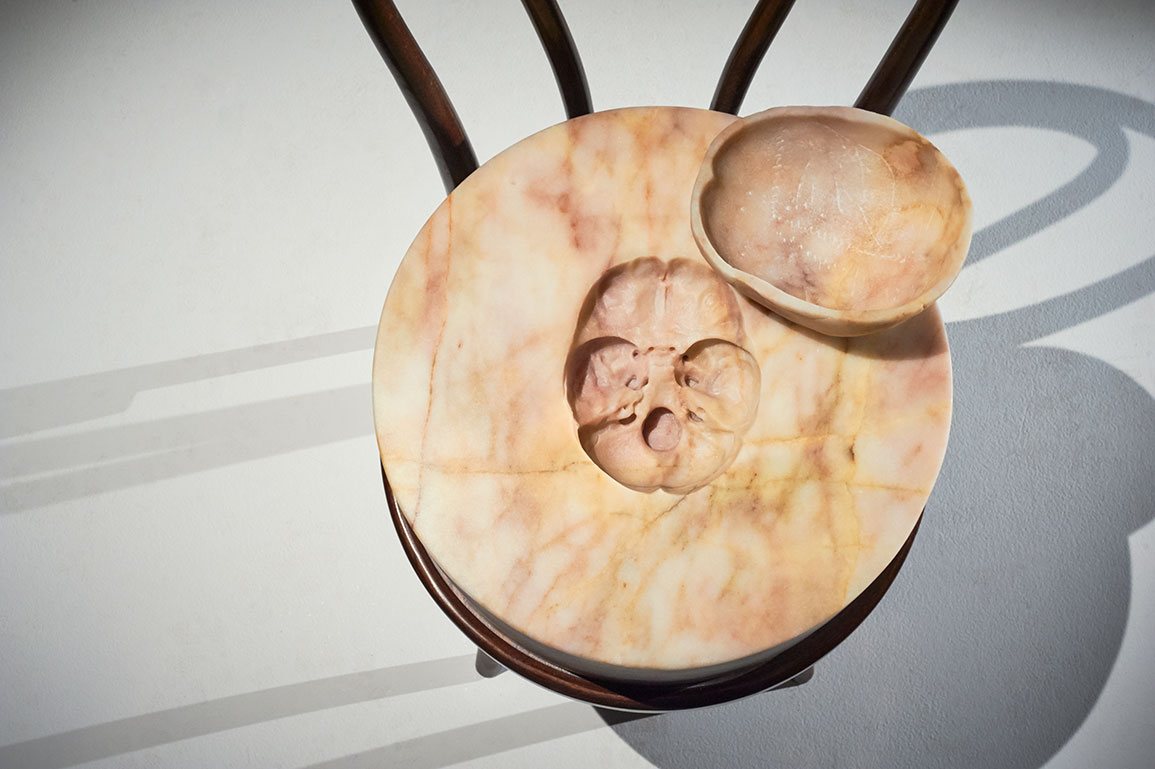

13 works centred around bentwood chairs and stools, each one based on the No. 14 creation of designer Michael Thonet in the 19th century. Alex used a medley of antique and modern versions of the No. 14 for a set of works expressing colloquial elements.

In Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book X, Pygmalion was a sculptor who made an ivory effigy of his perfect woman. He named her Galatea. He fell helplessly for her, prayed fervently that she be made human. The Goddess Venus answered his prayers. The ‘Pygmalion effect’ is the occurrence whereby greater anticipations lead to an intensification in performance. Its antithesis, the ‘Golem effect’ is the corollary consequence; in which low expectations results in a significant drop in performance. With these two themes, the artist swaps antique and modern bentwood apparatuses with his familiar medium of marble and digitally produced plastic alternatives. This then emerges as a series of crossbreeds where the mass produced fuses with the hand made.

Remarkable works, these, and one which has become a perennial favourite is the disturbingly-witty/ wittily-disturbing ‘There’s no accounting for taste’. It is a reference to Charles Dickens’ Sam Weller sayings, or Wellerisms, in The Pickwick Papers. “Everyone to his own taste,” the old woman said when she kissed the cow. But it is nothing what any sane person would expect: on the unsuspecting chair, an inflatable sex toy, of a cow, lies torpid, waiting to be ‘aroused’. This is just one example of Seton’s crazy sense of humour which ‘infects’ so much, you want to stay longer and converse with that strangely-seductive creature.

“I’ve come to explore all manners of materials; there’s a thing that happens with object-making, where you can distill your idea into an essence, but also have a physical interaction, and the thing which fascinated me most of all, was to have an object be multiple things at the same time.”

John adds, “Well I think most people first got to know of your work is something like Sculpture by the Sea; the lounge chairs and leather boots that gave people a real jolt - just that simple idea which looks like one thing but is actually something else.”

“What do you want people to see?”

“I want them to experience the contradictions, that initial idea of engagement, before external thoughts are brought in. For Pygmalion, I use the classic bentwood chair as my starting point. The initial design was so successful because they could pack these in a hundred and fold them metre by metre; the very first effective IKEA if you will.”

Taking in Pygmalion, I had to ask, “What was your childhood like?”

“My parents were particularly interesting individuals, adventurous, and they question everything. Most of my friends came from everywhere, it was very diverse. My early works as a child were all in aid of helping mum in her anti-nuclear protests.”

A print version of this article was originally published in d+a issue 96.

Share

Share