In March 2025, Architects, not Architecture (AnA) held their inaugural Singapore event in partnership with JUNG, gathering three notable architects on the Studio stage of Singapore’s School of Art (SOTA) to talk about themselves, rather than their work. This format gave attendees a unique opportunity to hear personal narratives and life experiences that have shaped the careers of Richard Hassell, co-founding partner of WOHA, Elora Hardy, founder of Bali-based IBUKU and Charu Kokate, senior partner at Safdie Architects, and how they have impacted the way they see their work.

With the focus on storytelling, the programme motivated the three prolific speakers to look at the ways they see their work as part of their lived experiences, and how they think these projects impact others in the same way. They discussed their past, their passions and how their work hopefully builds communities and encourages others to look to the future. d+a covers the highlights of the talks.

Richard Hassell – “Being a good ancestor”

Known for their biophilic designs, WOHA was started by Richard Hassell and Wong Mun Sum in 1994. Since then, it has gone on to win awards for its striking eco-hotels such as The Parkroyal Collection - Pickering and Pan Pacific Orchard.

For Hassell, many of the ideas and inspiration found in his work came from his childhood. Born in Perth, Western Australia in the 1960s, he describes it as an ideal place to grow up, with lots of sunshine and nature to explore as a child. Hassell’s parents encouraged him and his sister to explore nature and ask questions.

His father, a botanist and animal lover, had a strong influence on his interests in sustainability as well as nature, science and patterns. He spoke about repetition and difference, and how these simple components can make a surface interesting. A collector of strange objects, Hassell has noticed these objects will appear in his work years later unconsciously. “[Art] can just grab me and then also seem to get stuck in my head,” he said, giving examples such as Richard Serra’s sculptures which have appeared in the MRT Stadium station designed by WOHA, as well as Piranesi, which appeared in the design of their Bras Basah station. “I think all architects have a Piranesi phase,” he joked, referring to Susanna Clarke’s novel that imagines vast and unending hallways and vestibules.

Considering the future is inevitable when it comes to architecture, and this is something Hassell has spent time contemplating. “I do feel as architects, unless we have a solid grounding of what we think the future should be like, we just end up being reactive and responsive to daily activities,” he says. He mentions a quote by Jonas Salk featured in Roman Krznaric’s book The Good Ancestor, which quickly became a running theme throughout the AnA presentation. “Our greatest responsibility is to be good ancestors”. To that end, he mentioned working with the NUS economics department to create a suite of tools that can calculate the value of public spaces to show their long-term value. “The present is something we’re borrowing from our descendants,” he said, “and I think a lot of short term thinking at the moment is [what makes us] terrible ancestors.”

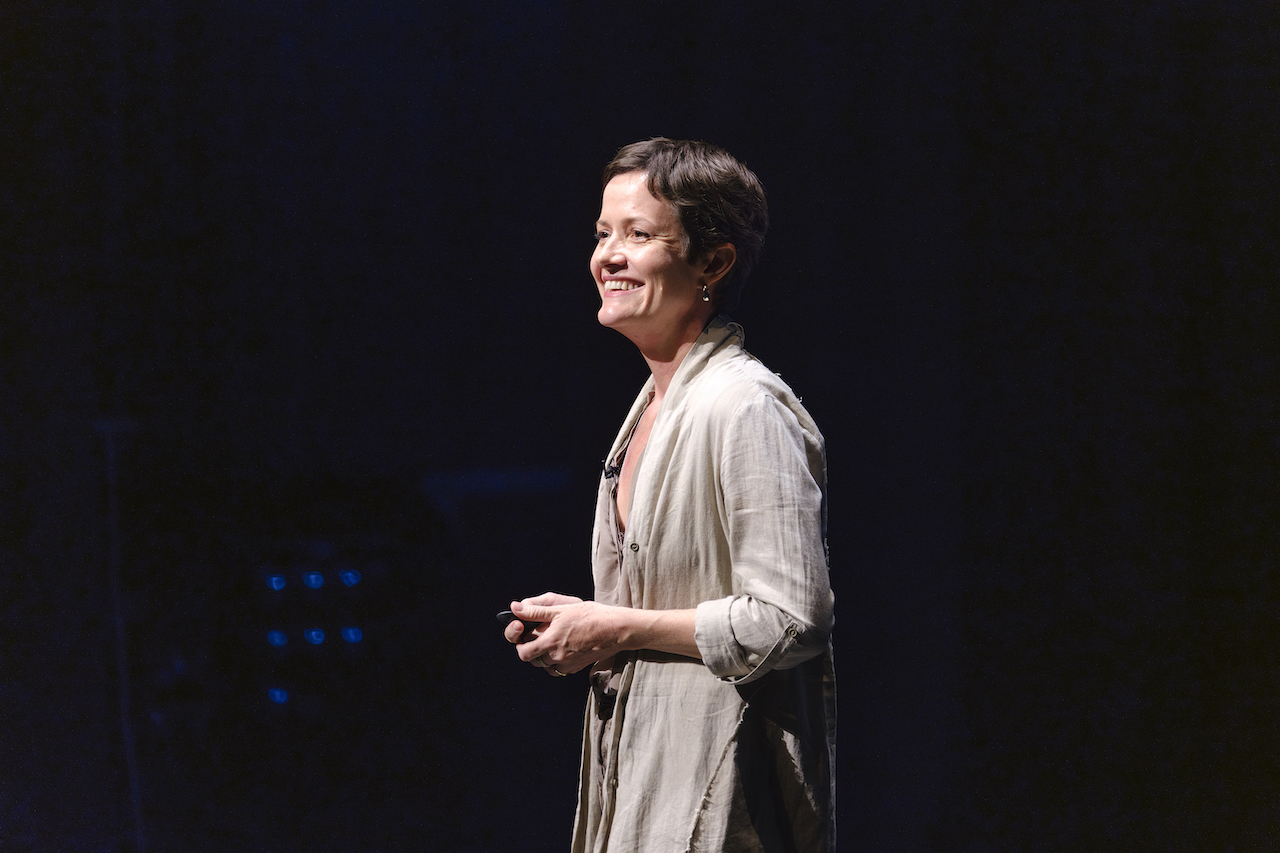

Elora Hardy – “The Bamboo Fairy”

As a child, Hardy lived in Bali with her parents until she turned 14. This experience, and her return to the island 16 years later, had a big impact on her fascination with a sense of belonging and what that means. “How do we keep our roots while doing what we want to do, and become who we need to be?” she asked.

Even at a young age, her ideas were treated seriously by her parents and the artisans they worked with. Telling of how her mother built her a “fairy mushroom house”, she says, “I didn't realise at the time how unusual or how special it was that she took my drawing seriously.” This first taste of acknowledgement and collaboration would go on to play a big part in her life. “You might know that feeling,” she said to the room of industry players, “of having an idea, then working together with someone to realise it - I got that feeling early on, and I'm still chasing it. It’s still a part of everything that I do.”

After completing her studies in the United States, Hardy went on to work as a print designer for Donna Karan. However, she found herself missing the lush greenery of Bali and returned to help her father and stepmother work on the creation of The Green School, famed for its sustainable, giant bamboo structure. “I thought it was insane,” she laughed. “But this building represented their future, something they could build their dreams on.”

When her father went on holiday to Europe for the summer, she found herself responsible for 130 designers, builders and artisans. “It was an extraordinary group of people,” she recalled.

A natural material like bamboo moves and functions differently. “There's no precision,” said Hardy. “There's no ‘typical’ because this is not a two-by-four. It's tapering and it's hollow and it's not even round.” Working with bamboo enhanced her understanding of flow and cyclical movement. “The waves of the interconnection, the idea of who belongs where, it really interests me,” she noted. “The sense that any sort of space or physical building has the chance to help you – in a given moment or in your whole identity – feel like you can belong, is important to me.”

IBUKU means Mother Earth, a name designed to evoke home, safety and connection. At the time, Hardy said she had no concept of what it meant to be a mother. But now, as a mother herself, she finds more meaning in the name, especially in relation to the experiences of her own mother, who passed away from breast cancer not long after Hardy had her second child. “I'm just beginning to understand what she went through, the challenges, the logistics, the international life, while I frolicked in the rice fields and through fairy mushrooms, she made room in her creativity for me to design my house. Parenthood is demanding and chaotic. In many ways, leadership is also these two things. It’s disorienting and beautiful. But it really has to come down to what's really worth doing.”

Charu Kokate - Building Connections

Charu Kokate began her talk with a challenge – is it even possible for architects to talk about themselves without mentioning the work? “How is it even possible to talk about our life – where every minute has been only for these projects? How do you separate yourself and call yourself an architect without your architecture?”

The senior partner of Safdie Architects, renowned for their work on Marina Bay Sands as well as Jewel Changi Airport, focused her talk on people – the ones who impacted her life’s journey as well the ultimate recipients of architecture. She opened with a story about Marina Bay Sands. “A group of us had moved from Boston to Singapore, and we had spent four years working day and night,” she recalled. “At the grand opening, we were standing in the hotel close to the casino side, watching the expressions of awe on people’s faces. The ceremonial gong rang announcing the opening – and suddenly hundreds of people pushed us aside and ran into the casino. It was not our building anymore.”

While she laughs at the anecdote, it was a reminder for herself, and everyone in the room how miniscule the role of an architect really is. “Projects like these can really define a career,” said Kokate, “but they do not necessarily define your life.”

Kokate went on to speak about her family. As the first grandchild, she occupied a special place for her grandfather, who would often tell her how special she was and that nothing could take that away. “I didn't really grasp the impact of those words at that age, but I believed it, and that belief really instilled in me a sense of self-worth,” she said. Growing up in a small village in India, with three younger sisters, Kokate’s parents were also instrumental in fostering that self-belief. “My parents basically told us gender was no limitation. And I think as a child, this helped me to build confidence and really impacted the way I have made decisions in my life.”

As a student in university, Kokate disliked the emphasis on being the sole creator of a design. “This is not true of the real world,” she said, noting it puts unnecessary pressure on students. “Architecture is such a complex process. It's not a simple, small thing. When you look at a project, there are different stakeholders, everybody has conflict in use, everybody wants something different.” A good architect, she counters, has to be more than a good designer. “You need to know how to work with people, how to understand them and how to bring them together. Design is but a small aspect.”

She cites Indian architect Sharukh Mistry for emphasising this to her. Renowned for buildings that enhance and build communities, he believed that architecture must fulfil the needs of the people and their ambitions. This philosophy was echoed by her boss and mentor Moshe Safdie. When she initially did not want to be involved in a casino project, his advice to her was “Look at the spaces you're going to create for different people, and do not get hung up on the tags.”

The people-focused philosophy was something she has honed throughout her careers creating mega structures. “I've learned that architecture is not just about buildings. It has really become for me, understanding the needs of people and convincing them of the vision that you have. You have to inspire them to believe in what you're saying and make it work.”

Share

Share