The DesignSingapore Associates Network (DAN) has a new president and he is one personality we should all keep an eye on.

Syafiq Jubri took on the position in July this year, on the back of his return to Singapore after spending nine years in the UK, first studying then working as an architect.

The organisation he helms is made up of scholars from the DesignSingapore Council (Dsg), allowing them to network with each other, seek mentorship and collaboration opportunities and promote Dsg’s initiatives.

Naturally, the 30-year-old is also a Dsg scholar, enabling him to obtain his Masters degree from the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London fully funded.

“I took on the position because it was an opportunity to bring together like-minded communities. Also, it is a way to re-familiarise myself with Singapore, since I feel I am in between cultures right now,” admits Syafiq, as we sit down to an interview at the National Design Centre (NDC) one afternoon.

Dressed stylishly in full black with a pair of clear spectacles, the lanky Singaporean looks every part the designer.

Despites its youthfulness – the DAN was only established in 2018 – he feels a good foundation and structure has been laid for him to build upon.

“This year, apart from doing networking events with scholars, we are pushing for two community engagement programmes I’ve themed ‘Doing’ and ‘Speculating’ that will feed off each other,” he reveals.

The first theme is focused on bringing design outside of Dsg home at the NDC, such as to the heartlands, to increase its visibility and accessibility.

“Through the process, we might learn a thing or two about different design communities around Singapore.”

The second theme will centre on the idea of craft, an extension from last year’s efforts, examining its future in food (and coincidentally, a theme at this year’s ArchiFest).

“We want to continue this by exploring the use of technology in Singapore’s public spaces, and speculate what they could be, imagining alternative scenarios for them.”

Successful Failure

Syafiq’s unconventional ideas hint at a multi-disciplinary mind that becomes more apparent as he shares about his life journey.

For starters, he is refreshingly upfront about his chosen career path, “Architecture is this mask for me to sound professional. Deep down inside, I'm a closet inventor. I love making things. I love to understand how things fit together and work.”

He recalls taking apart radios in his childhood, and a deep-seated love for Lego and Tamiya racing cars.

When he failed Mathematics in secondary school, he was posted to study Design and Technology (D&T) instead, where he excelled in and eventually topped the class.

“It came naturally to me. It was quite easy for me to draw something three-dimensional,” he says, with an embarrassed laugh at his disinclination towards numbers.

After learning that he could put these skills to good use in the Interior Design course at Temasek Polytechnic, he applied for it and got in.

It was there that he learnt about Archigram, the influential British architecture collective formed in the 1960s, leading him to dip his toes into the subject.

“It shaped the way I was thinking about spaces – that when you're creating an interior or external space, it's not just floor and walls that defined the spaces, but the smell, the site, the all-encompassing experience that actually creates architecture.”

However, after two brief stints in interior design firms, he concluded he was not made out for the work.

“I was interested in how structures work, how you put materials together, how you make things stand out with emotion of some sort. I felt Architecture ticked those boxes better.”

In 2010, after serving National Service, he left Singapore to study Architecture at the University of Sheffield.

Britain Calling

He labels his education at Sheffield as a mix of “happiness and frustration”. On one hand, its pragmatic syllabus enabled Syafiq to build a strong foundation in the basics of Architecture.

“One thing which I did not foresee was that they had a very strong social agenda. My view on architecture had been quite technological and scientific up till then.”

For instance, in the planning process of designing a building, architects working in the UK have to conduct consultation sessions with the community it will be in.

This meant that a concept that could be celebrated in an architecture magazine, could “look too scary for the community”.

To solve this, architects would have to design a few different options and put them to a vote.

Upon graduation, he spent a year in Cullinan Studio (London) as an architectural assistant helping out on projects like a residential block in Bristol and Camden, London.

It was then that he learnt from friends back home about the Dsg scholarship and decided to apply for it.

“Dsg was looking for new scholars to learn new skills in non-traditional fields, such as user experience, service design and digital design. I guess this is how they question and challenge traditional practices.

“Through the Design 2025 Master Plan, they have identified contemporary world issues are multi-faceted. I felt that this is quite interesting, because it's going beyond the idea of really creating a building, which is similar to what Archigram did.”

Challenging Convention

Syafiq chose the Bartlett School of Architecture after realising one of the co-founders of Archigram, Peter Cook, was a key figure in shaping its curriculum as its director.

He laughs about this serendipitous turn of events and being slight star-struck when meeting Cook on campus.

His two years there completely overturned everything he had learnt about Architecture. Among the things he was exposed to was the constant questioning of how the profession can be practiced differently.

His tutor, Nat Chard, was a professor in experimental architecture, whose PhD thesis was about creating instruments that would splash paint onto paper and then labelled them as architectural drawings.

“By creating these instruments, which are very, very precise, and splashing the paint, which is quite a random act, he questioned the types of similarities to how architecture can be inhabited. It’s very deep in a poetic sense,” he muses.

Syafiq observes that architectural education in the UK is quite divorced from practice, but it is something that is preferred, “We are both challenging each other. Students don’t actually train to be in practice, but what practice could be. It's very liberating.”

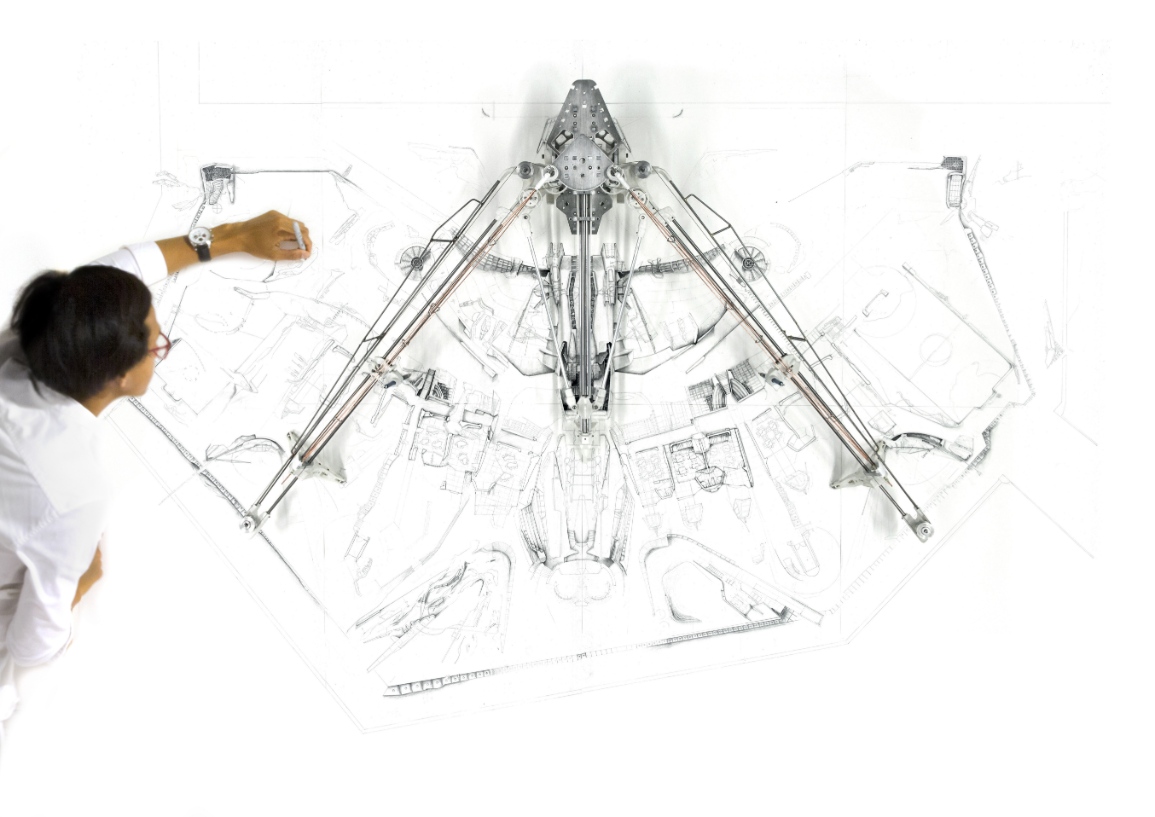

It is not surprising then that his own thesis is equally abstract: to hack his own hand drawing.

He did this through designing a drawing instrument, AnnA, that allowed him to use both his hands to draw simultaneously, a proposal for a primary school.

“I wanted to explore of this drawing methodology be of value to architectural production. Conventional teaching practices are depicted with my right hand and alternative forms of education with my left. Where the right follows the rules, the left encourages a process of questioning them, stimulating both cerebral hemispheres.”

His project – a sizable one measuring 2.1m by 1.5m – was displayed at the Making Architecture exhibition in October, as part of ArchiFest 2019.

Que Sera Sera

Syafiq spent a further three years in London working at Tate Harmer and teaching at Bartlett before returning to Singapore in July this year.

Another motivation for his return was to fulfil the requirements of the Dsg scholarship. Scholars have to work in Singapore for two years in a field related to their studies within five years of their graduation.

In addition to presiding over the DAN, he is currently self-employed as an architect, and teaching as an adjunct lecturer at his alma mater Temasek Polytechnic and the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

It is always interesting to hear from the younger architects on where they think their profession is going.

Syafiq pauses, uncertain about the answer. He is sure that the role of the architect as prescribed by the board of architects will be the same.

“We have quite interesting skill sets and it remains to be seen where it will take us, especially into the sub-branches of design and architecture. I think we could become more like innovators.”

Personally, he hopes to someday be able to put his hands to good use again.

“There is this saying that architects make images not buildings, because we create a set of instructions for builders to build it. We don't actually create the buildings.

“But then that’s the thing which I am sometimes a bit deprived of. If I want to build a building, I want to build it with tools, my own hands.”

Whether Syafiq’s aspiration will come to fruition remains to be seen. But it will definitely be worth watching out for.

Share

Share