“Provocative”, “broaching new frontiers”, “thoughtful”.

These were some of the adjectives used to describe The Factory, the winning entry of the Nippon Paint Asia Young Designer Awards 2020/2021 Architecture category, submitted by Eldon Ng from the National University of Singapore.

This year’s competition was themed “Forward: Human-Centred Design”, where the brief was to generate and share ideas around concepts made with people in mind.

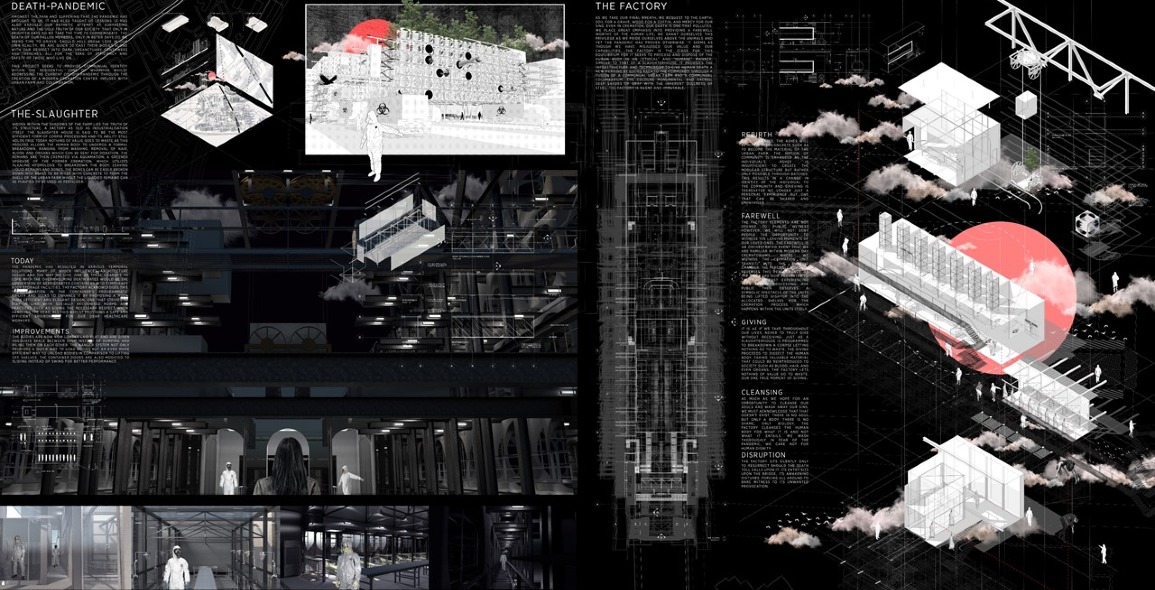

Ticking the boxes was Ng’s project that puts a fresh spin on the crematorium, providing dignity to the deceased, while addressing issues of sustainability and circularity.

A particularly controversial idea: purifying human remains for use as potential fertilisers for farming.

Ng even makes space for philosophy, questioning the human behaviour of placing ourselves on pedestals and whether at the end of the day, we are truly more superior than other living things.

These are what prompted juror Melvin Keng, Principal Architect of Kaizen Architecture, to say of the entry, “In the middle of COVID-19 difficulties, death has been an inevitable part of our reality, but Eldon was able to tackle it head-on and not just incorporate it into everyday architecture in a respectful, sustainable way, but also celebrate this facet of human existence.”

We caught up with Ng to find out more about The Factory and how he came up with the idea of tackling the taboo topic of death.

How do you feel about winning the award?

I was shocked upon hearing the results. I really wasn’t expecting a win – in fact, I didn’t think it was even possible because of the topic that I was addressing. Death isn’t widely discussed, especially in a fairly conservative nation like Singapore. Furthermore, I was aware of the various cultural norms that may be challenged by my proposal, especially in a racially and religiously diverse nation like Singapore. Though I did my best to resolve and tackle these concerns, I still held doubts that my project would win.

I am definitely grateful for the semester I had with Professor Bobby Wong. He allowed me the freedom of thought and expression, while encouraging me to continuously question the norms of today. My semester could be summarised as an amazing discussion with him on this supposedly morbid topic. Moving forward, I also hope to develop The Factory into a more personable project, allowing our need to grieve to be better satisfied.

You had some early thoughts around the idea of identity and giving in light of the pandemic. What were they and why did these themes intrigue you?

I think it all started as early as the beginning of the pandemic, back in the second half of Year 2 Semester 2. This was when we had our first taste of what the pandemic was doing and how it affected studio life. We all sat anxiously in front of our laptops as we watched the Prime Minister give his speeches, especially on whether schools would be closed. It was in those moments that the impact of the pandemic truly hit us as students – that our lives were never going to be the same, whether temporarily or permanently, that uncertainty was going to become certain in our everyday lives.

I remember those moments where we all clapped while at home for our frontline workers, and even sang National Day songs. It was then I felt that desperation in humanity to be connected with one another, to provide aid, support and love, to basically feel less alone and that thought stayed with me into the new semester, Year 3 Semester 1, where this project was conceived. I believe this was when the idea of communal identity truly originated and Prof Wong brought about this question in the semester, “How can such a simple task of empathising, sharing and being together be expressed and carried out in light of the pandemic? How different would it be?”

It was in that moment where the thought of death came to me. It truly is something we are all fearful of, something that equalises us, something that the pandemic unfortunately highlighted, something we can all relate to emotionally. Hence my approach, to forge identity and communal spirit through it.

Can you elaborate more on how The Factory offers a hopeful twist of giving back to the community? Is it purely through your proposal of the harvesting of organs?

The early stages of the design were focused not just on organ donation but really to save on land use. The reality is people die every day. Graves, columbarium and space are needed and this number never declines. We can’t afford to continue occupying land for these facilities, there has to be a more economical way. In this aspect, I was really questioning how we as humans continuously take from the environment. Even in death, we shamelessly ask the Earth for resources – the process of cremation produces greenhouse gases. Hence, have we truly ever given back? A lot of these ideas stem from an ecological point of view. Organ donation was derived as part of a measure to reduce the overall mass needed to be cremated in hope of producing less greenhouse gases, and of course, save lives whenever possible. The other twist of giving back comes from the liquified remains of the ‘aquamation’ process, where the remains can be purified for use as potential fertilisers for farming. That of course is something much more debatable as there are both studies that support and oppose this idea, assuming people are even accepting to the idea of eating such produce.

How does The Factory hope to provide more dignity to the deceased?

As reported in the US and various other countries/states, there seems to be an inability to cope with the overwhelming death rates. There are those who turn to storing of bodies in containers and in more extreme cases, mass graves. In both methods, it would appear that dignity in death is clearly secondary to the efficiency of disposing bodies. In light of this, I felt that dignity could be restored by first improving these temporal strategies by better designing the infrastructure of the disposal of bodies.

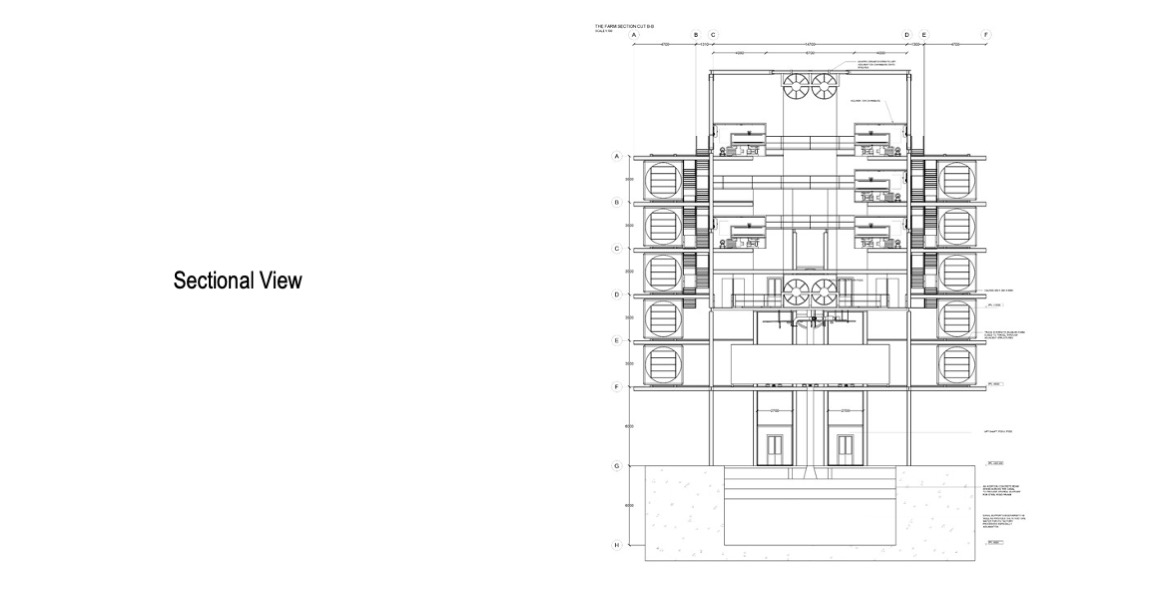

Also, since there is an overwhelming death rate and insufficient time allocated for individual families to grieve, perhaps we could grieve via a communal approach. I envision the multiple cremated remains used as materials to construct an urban farm pod, and in that single pod, it symbolises those that have passed in perhaps batches. In a way, the dead become an architectural form that no longer addresses the individual’s dignity and identity, but rather a communal one. This was in fact one of my key concepts in creating a communal sense of grieve and identity.

How have you designed the space so that it comfortably accommodate the living and deceased in what could otherwise be a cold and sterile setting?

In the semester-long discussion with Prof Wong, we felt that there wasn’t really a place that could truly be accepted by the general public. In fact, towards the end, we settled that this should be a government initiative, which is not accessible to the public, except for a single location which I called the Farewell. The Farewell is the space located near the end of the structure, where the theatrics of the aquamation pod is hoisted into its shelf. This was my recreation of the common cremation practice, where we witness the coffin being moved into the furnace via a conveyor belt. I imagined this to be an extremely heart-wrenching moment and the space is entirely opened towards the sky as a symbol and expression to our loved ones leaving us to a better place. The farm pods are then the physical remains that become quite literally what is given back to society through the production of crops/edibles.

You say that The Factory questions the current behaviour and attitude of humanity itself. What exactly is it questioning?

The pandemic didn’t just question of preparedness. In fact, that is probably one of the smallest questions. If anything, the pandemic reminded us that we are but a fragment of nature, that we are somehow biologically interconnected, and even with our great intelligence, we can never escape this truth. It questions where we stand as an organism, as a being; we consistently place ourselves on pedestals thinking that we are different from other animals, yet we are mere pieces of a puzzle. Just as everything in Nature, there is an end and we shouldn’t glorify our end unnecessarily. If we saw ourselves as truly mere organisms that are here temporarily, how would we behave?

Can you share how you think The Factory can be improved through better use of materiality and architectural forms?

Perhaps the creation of farm pods was forceful to the idea of giving back. Perhaps it would be better to use the remains of the deceased as materials to construct better spaces that are actually occupiable and experiential. Perhaps that would be a better way of giving back dignity.

How does The Factory offer purpose and hope?

My earlier answer seems to suggest that there might be no greater meaning in life. If we were really mere organisms and temporal beings, what exactly is the point of existing, is death all that awaits? In light of this question, my design hopes to suggest that we are all capable of giving and providing to the world and those who come after us. As individuals, in our lifetime, we might not attain nor understand what we have lived for; but perhaps in our action of giving, it might lead to the fulfilment of another’s life.

Share

Share