The Cambridge Dictionary defines a prototype as “the first example of something [...] from which all later forms are developed”.

In this context, if we approach architecture as an object-making process, then – barring some 1:1 scale prototype of some small parts or details – it doesn’t really have a prototype, because the final product (which is the built environment) is the prototype.

For the longest time, scaled models were the closest thing to a prototype in architecture.

Today, we have a more immersive tool: Virtual Reality (VR).

In its early days, VR technology came at the tail-end of a built architecture project, after design and documentation processes, usually as the centrepiece of the project’s marketing campaign.

The advent and subsequent availability of BIM (Building Information Management) has helped architects to integrate VR into both design and documentation production streams.

No longer must architects split their time and manpower to produce items for both streams – they can document while they design.

No longer do they need to complete the design and documentation processes in order to produce the VR campaign – the VR is the platform on which they can collaborate.

Architects Regain Control

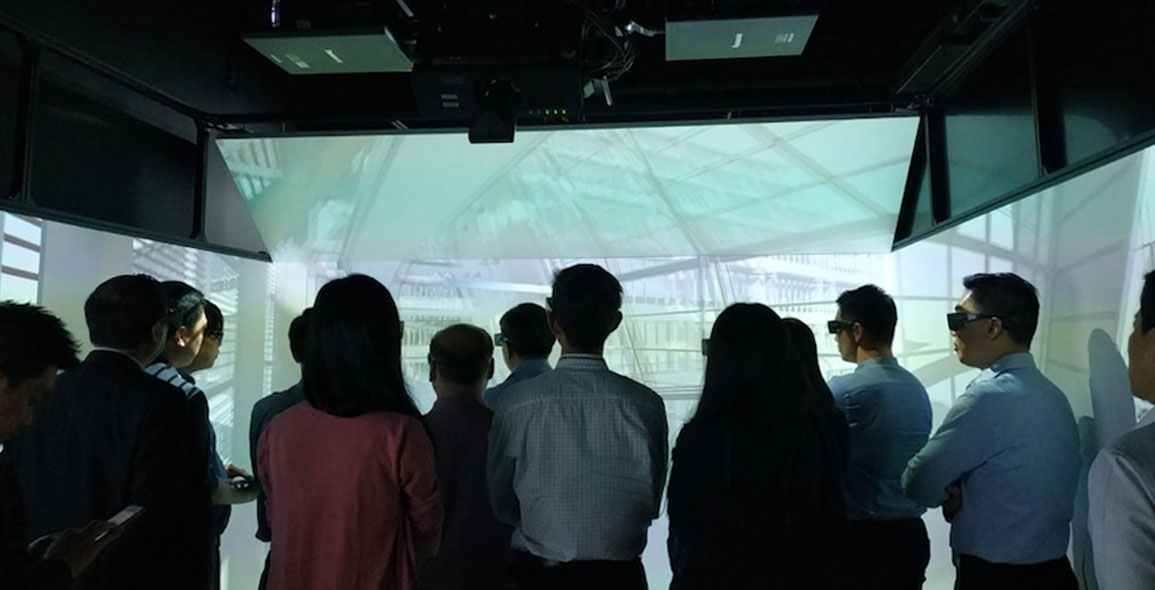

First developed and flourished in the gaming and entertainment industry, VR technology has become ubiquitous in architecture, construction and engineering industries – be it as a tool for an internal design review, or cross-discipline collaboration between consultants.

It is a highly effective tool of communication between those who speak the technical language of design and those who don’t.

What then is the outlook for VR in architecture in 2020 and beyond?

Ryan Liew, Chief Operating Officer of VRcollab, a Singapore-founded tech firm that supplies VR technology to architecture firms, sees two global trends that have been spurring the use of VR in the architecture industry.

One is the increasingly complex, hybrid-typology architecture projects being built, and the global increase of BIM take-up, via private and government-mandated initiatives (like in Singapore, via BCA).

“I believe the most important progress ahead would be for all stakeholders to have a more collaborative process with trades other than their own,” says Liew.

The original meaning of the word “architect” is “master builder”.

Yet, in the digital age, often the architects are just one of many consultants involved in a project, and their voice may end up diluted or lost in the increasingly complex production stream.

VR technology is one of the ways for architects to regain that master builder role, to have more say in the project by creating a platform that can best communicate their vision to their collaborators.

“In the past three years, the high cost and the cumbersome nature of VR setup have been the key barrier to the greater VR adoption in our industry,” he adds.

There is also a general reluctance to don a VR hardware attributed to fear of isolation and ridicule, he says.

Dubbed “head inertia” by the VR community, this fear is an additional factor that slows down the take-up rate of VR in the built environment industry (as opposed to VR’s popularity in the gaming industry).

But Liew sees a global uptake in the use of VR in this new decade, “Fast forward to today, VR hardware has become more affordable, and designed as a plug-and-play feature.”

Other than improvements to audio and control features, Liew forecasts no drastic evolution in the next five years in the design of the VR hardware, though industry demands for a shared and editable environment between two or more users are on the rise.

The latest suites of commercial software also play an important part.

One of these is Enscape, a real-time rendering and VR plugin launched by German company Enscape GmbH in 2013. It is compatible with Revit, Sketchup, Rhino and ArchiCAD.

Simply click the Enscape button to view the model on screen or in VR via the hardware.

Describes the company, “The beauty of Enscape is that all the prep is done in your familiar BIM tool and all subsequent edits are automatically seen seconds later — textures, lights and all.”

According to Liew, there are three key selling points of VR in architecture: enabling consultants to experience the building before construction, testing the visual aspect of the material selection in scale, and detecting “soft clashes”.

The latter refers to design features that look technically correct on a 2D medium (screen, paper) but present issues when tested in a 3D virtual environment that needs tweaking to suit end-users.

“We see our customers as collaborators, and every feature, improvement and product update are made by listening to our customers,” he adds.

But there are other advantages too.

“The use of VR is to provide an interface to BIM, to represent the information in an easily accessible format,” says Gerard Teo, Chief Technical Officer of ID Architects.

“Despite being ubiquitous and critical in the construction industry, BIM is not always accessible to most of the stakeholders in the construction process due to a variety of factors, such as the disparity between industry professionals and BIM capable technicians, and a high barrier to entry to BIM information due to the prerequisite software skills.

“VR allows the democratisation of the data held in the model to stakeholders in the construction project.”

ID Architects is one of the first architecture firms in Singapore which developed its own VR software.

“When we embarked on leveraging VR in the construction process, we realised that the tools available in the market did not necessarily meet the requirements of practitioners in the industry as they were mostly generic solutions adapted across other applications,” Teo shares.

To develop a solution for architects made by architects and reclaiming architect’s role as the master builder, IDA spun off tech firm IDA Technology to “further develop the tool, and to propagate the tool to other stakeholders in the industry”.

Teo elaborates that VR cannot be used in isolation, “VR technology would need support from all parties in the building industry for further innovation and development.”

In the future, BIM with integrated VR/augmented reality will continue to be a powerful tool to develop, manage and operate the built environment.

“IDA will continue R&D in this area. We have a vision for a building industry that imagines various stakeholders implementing VR technology in their respective areas – developers would create VR showrooms, building operators VR training rooms, contractors VR mock-up rooms for material approval and so on.”

Whether this will become a reality remains to be seen. But one thing is for sure: the application of VR in architecture is very compelling and this is one bus no architect should miss.

This story first appeared in d+a's Issue 114: February/March 2020. To read the rest of the magazine, purchase and download a digital copy from Magzter.

Share

Share