As Singapore’s population burgeons, and competition heats up for whatever space is left in the land-scarce country, the question of setting aside square footage for playgrounds comes to the fore.

This is the theme behind a new exhibition that has just opened at the National Museum of Singapore (NMS), titled The More We Get Together: Singapore’s Playgrounds 1930 – 2030. Leading the conceptualisation is RSP Architects Planners & Engineers, with senior associate Mark Wong as the team lead.

Over 16 months, he worked with the museum and his colleagues to flesh out the subject and put together a narrative that explores the past, present and future themes. Beyond their obvious use for fun and games, public spaces such as playgrounds also define our society’s identity and heritage.

Wong describes to d+a the thought process behind creating the exhibition and his ideas on what the future of playgrounds looks like.

Mark Wong (in light grey) and his team

Mark Wong (in light grey) and his team

What interested you about this project?

This is a subject we feel deeply about. Singapore's playgrounds are not only so prevalent in our landscape, but they also hold a unique place in our people’s hearts and history. Once we recognise that the playground is a designed social space and cultural artefact, it becomes evident why this exercise is important to us in the business of delivering architecture, urban design and masterplanning.

This is, after all, quintessentially what we do on a daily basis: craft meaningful spatial experiences that will be used and remembered by its many users. So the opportunity to contemplate the history and future of this very small but very impactful urban programme with NMS is a wonderful opportunity for us, and we very much look forward to watching it inform our own design of public spaces in the future.

How were you personally involved?

Since the nascent inception of the project, the curatorial and design teams have collaborated very closely in every aspect of framing the exhibition’s narrative and experience. The design team comprises three designers (myself included) who have been actively working with NMS on this project since as early as 2016. I think I’m the glue that musters different ideas and talents to form a better sum of parts. My slight advantage in delivering more projects makes sure that we are able to bring our collective vision to built form.

How did you come up with the final concept for the NMS exhibition?

The most important and interesting aspect of this show is that it is actually a very forward-looking, aspirational show. Even though a lot of history is uncovered and presented to the audience, it does not seek to hark back to nostalgia. Instead, the exhibition design, archival material and member participation segments all aim to spur viewers into assessing what and how they personally relate to our playgrounds throughout their own lives, then reflect and evolve those values and beliefs in the individual’s imagination of an ideal future playground. Because understanding our history is important for us to chart ahead, our work then is to introduce the many small parts that make the sum whole and greater than itself, and this can range from actual construction drawings, photographs and interviews of people experiencing the playgrounds.

We are also mindful not to present the show as a substitute for people visiting actual playgrounds. At the same time, we want to emulate play so that we can invite that sense of intrigue and fun that lends to more active learning, which befits the subject. This actualised in the show being very tactile and immersive, with reinterpreted elements that are very synonymous to certain periods of playground life.

Please describe the show in your own words.

The show is essentially split into four vignettes or epochs, each standing on its own as sort a micro-world at a different time of the day, beginning with the crisp freshness of a bright morning graduating to the mellow calm of the night.

- The brightly coloured artificial turf and morphing ceiling panels in vignette 1 (“Singapore’s Early Playgrounds: 1920s – 1960s”) are mirrored infinitely through the walls to exaggerate that expansive land and skyline of a much younger and less built-up nation.

- The pixilated walls of vignette 2 (“Playing in the Neighbourhoord: HDB Playgrounds (1974-1993)”) obviously elude to the mosaic walls of the concrete playground structure so definitive of that era, but the memory wall that seeks audience feedback recalls also the many “I was here” graffiti that are left by occupants at these playgrounds.

- Vignette 3 (“Making Fun and Safe Playgrounds a Business: The Rise of Singapore’s Proprietary Playgrounds”) has its floor fitted with rubber mulch and features an actual play equipment as its centerpiece.

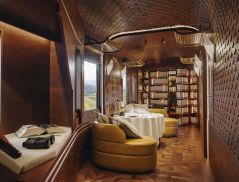

- The meditative last vignette, designed by a team of architecture students at Singapore University of Technology and Design, invites people to imagine the future in a stripped down space fit out with popular playground equipment reinterpreted as benches.

The different galleries from the exhibition

The different galleries from the exhibition

What do you think Singapore's community identity could evolve to become?

We certainly hope we can grow as a people who can accommodate and celebrate a variety of identities and voices that are always evolving, while upholding universal values like kindness, empathy, compassion, etc. That said, we also hope that our communities will one day be able to meaningfully contribute to the process of shaping our built environment.

What could the future of playgrounds look like?

Over the last year, the curatorial and design teams have been in touch with quite a number of people to discuss the future of playgrounds and we realised that many people have differing but equally valid concerns on the future of playgrounds. This has led the design team to believe that the future of playgrounds should not necessarily be embodied by a single idea or vision, other than that they should be a lot more democratic and inclusive.

This is to say that playgrounds can be a bit more varied in response to the needs and aspirations of the community they serve, and maybe more than one type of playground can be offered. For example, a playground can be targeted more to older kids and teenagers, so that the equipment can be a lot more challenging and aesthetically more relatable to them, whereas another can be designed more for toddlers who are accompanied by caretakers and family members, whose needs outside of play also have to be met in order to encourage their bringing the kids out to play.

We also realised that while the concrete playgrounds of yore, e.g. dragon and pelican, may not necessarily hold a sentimental place in everyone’s heart, they are however recognised as a part of our heritage and celebrated as something very uniquely Singaporean. With that in mind, we believe that there’s a lot of mileage in customising the designs of the playground so as to lend to and/or feed off the identities of the community. This can manifest in many ways: historical context of a community can inform the imageries adopted at a playground, or existing identity of the site or community can also be a point of reference.

All that said, this is, at the end of the day, about communities learning more about our histories, allowing it to inform our formulation of a vision forward, and taking more ownership in paving the way for how our environment manifests.

Why is this concept an important one for us to explore?

Playgrounds are, at the end of the day, social artefacts, thus reflecting a lot of our social mores and attitudes. For playgrounds to change, the way we allow our children and selves to approach play in public spaces can and has to evolve as well. Our playgrounds from the developing years addressed more basic and immediate needs, from having to provide a space for play in our urban environment, to establishing standards for maintenance and safety. But as our society advances, so must and will our people.

From our discussion with people, it seems as if almost everyone wants playgrounds to be more open and adventurous, so that users learn to discover, take a tumble but get right back up. The complaint often is that today’s playgrounds can be a little too sterile and devoid of challenge. But people will need to slowly recalibrate how they approach and manage risks at playgrounds, ceding less control of such matters to the designers and authorities, and instead learn to manage the risks together with their friends and family as they play together at these venues. If we remain too quick to point fingers at others, then we can expect purveyors of playgrounds to always err on the side of caution.

What do you hope to see more of in our public spaces?

There’s a certain joie de vivre that is lacking in our public spaces, which I think has less to do with the physical manifestation of the form, than the culture of our people, which is in turn moulded by a host of other factors like our upbringing, education, laws, sociability, etc. This makes the inhabitation and use of our public space less spontaneous and driven by far too few programmes and purposes (often commercially related), which in turn can limit the entry of people into these spaces. In time, we hope certain liberalisations can take place in our systems and our minds, that will not only allow for a much more lively and dynamic use of public space, but also foster people’s greater appreciation of it.

The More We Get Together: Singapore’s Playgrounds 1930 – 2030 is on show at the National Museum of Singapore from now till 30 September 2018. Admission is free.

Share

Share